How I Turned My Reporting Notes Into Book Funding: NFT Fundraising For Writers and Creators

A detailed guide to tools, workflow, and revenues.

In December of 2023, I held an auction for a series of NFTs I called “Rare Sams.” The NFTs were 15 unique drawings – so called “1 of 1s” – taken from courtroom sketches I made during the October 2023 Sam Bankman-Fried trial while reporting for Protos.

The sale was a modest success, grossing around $850 with nothing but word-of-mouth promotion. I’ve long been pro-NFT in theory, but this was a chance to put my enthusiasm into practice, and it really affirmed my enthusiasm: Despite a huge crash in public perception following the fake mania for things like Bored Apes in 2021-2022, I still think NFTs are a powerful tool for writers and other creators to connect directly with their audience and solicit support.

The following is a “How To” guide to creating and selling NFTs, and some points about what NFTs are really “for,” specifically for writers and creators.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Why issue NFTs?

Steps

Tools

Costs and Results

Pitfalls

The good news is that the tools to create and sell NFTs have become widely accessible to the non-technical. I used two services: Manifold and OpenSea.

Manifold is really beautiful and elegant, and even offers some tricks to save on mint fees. While OpenSea is *far* from perfect, it’s at least a standard Web interface that anyone with a bit of patience can navigate. There’s no need to do anything like coding, or even reading a blockchain (with a couple of unfortunate exceptions I’ll highlight below).

Probably the bigger challenge is simply deciding whether NFTs meet your goals as a fundraiser, and what role they’ll play in your project. In my case, the NFTs are acting as living “certificates of authenticity” for the real-world drawings.

Less important but notable, selling the NFTs via OpenSea and “including” the drawing also wound up costing slightly less in total fees than it would have to, for instance, auction the drawings directly via eBay. OpenSea’s own fees are *much* lower than eBay’s, but I’m including on-chain transaction fees.

One final note: Circa roughly 2021, during the initial wave of true NFT Mania, there was a lot of noise made about why artists shouldn’t make NFTs because blockchains use so much energy. In 2022, Ethereum transitioned to a proof-of-stake consensus system that doesn’t consume a notable amount of energy, so those arguments are now moot.

Why I Launched Rare Sams

The goal of my NFT sale was to raise money to support the writing of my book on Sam Bankman-Fried, “The Boy Who Wasn’t There.” Back in 2022 I made it my mission to explain to the public that he wasn’t merely a well-intentioned fuckup, but in fact a malicious criminal. Then in 2023, I got to report on Bankman-Fried’s criminal trial every day, in person – a trial that more than vindicated my and others’ worst speculation about what had actually happened inside FTX.

The idea of doing courtroom sketches emerged naturally from the situation – no cell phones, cameras, or video devices were allowed at the trial. It didn’t take long for bored reporters to start sketching, but stalwart CoinDesk reporter Nik De really got the ball rolling by sharing a few of his charmingly minimalist sketches, and even including some in CoinDesk stories.

With apologies, I’m at least a slightly more talented artist than Nik.

Other reporters in the pool started sharing their sketches, and things even got a little competitive. CoinDesk’s Danny Nelson probably won the whole thing by creating a “pop-up sketch” with background and foreground layers.

The point here is mostly that what you decide to base NFTs on should also be, ideally, organic and meaningful. Is there some symbol or character already associated with your work, for instance?

I also decided to include benefits with the items. I’m essentially writing my SBF book in public, sharing draft chapters as I go - but only with people who either subscribe through Patreon … or buy one of the Rare Sam NFTs. Buyers will also get a copy of the eventual book. This is all done manually, by the way, rather than through something fancy like token gating. Consider mine the most simplified, stripped down version of what’s possible.

The initial sale was a modest success, with six of the NFTs selling for around $850 USD worth of ETH – the native token of the Ethereum blockchain, where the NFTs “live”. That fell short of my wildest fantasies, and some significant costs ate into the take-home. On the other hand, I still have some of that ETH, which has climbed in value.

At worst, I made a bit of money while learning to do something new. I was also surprised to find that getting hands-on with blockchain tools was strangely satisfying – it genuinely felt like I was “making” something.

I also still have nine of the NFTs, which I’m putting back on auction in conjunction with this post. I’ve had a lot of people express interest in them after the initial auction, which also helps put my results in context: I’m terrible at promoting and marketing things, so someone with more talent there could have far, far more success than I did.

Why NFTs?

NFTs are fantastic if you’re trying to raise money for a community-minded project that has broad support. They’re cheap to create and deliver, and act simply as social proof that someone is an actual supporter of a thing. There are a growing number of gallery and other display options, but the fundamental attraction is that these are digital objects, a status I talk about in my essay on Marshall McLuhan and blockchain. Owning them isn’t mediated by any third-party service. They’re “real,” and they’re permanent.

Public Funding: The best example of this use case, and the favorite NFT that I personally own, are Poolys. These NFTs were sold to fund the court case defending PoolTogether, a lossless lottery and one of the most interesting projects going, which was targeted in a frivolous lawsuit by a former Elizabeth Warren staffer. Because the plaintiff essentially faked his standing, that suit has now been dismissed.

But it might have been a much bigger burden for PoolTogether without funding from selling these little guys. They don’t have resale value. They don’t have utility. They’re just fun little mementos for something I would have supported anyway.

This sort of good-faith donation, to my mind, is the ideal use case for NFTs. They’re at their best when they’re truly sentimental and community-oriented, rather than some complex financial scheme (I’m an idealist, I know).

This is largely how I hope Rare Sams work, though for now they’re targeting a higher-dollar supporter than Pooly, due to both 1-of-1 uniqueness and physical media costs (see below).

Provenance Tracking: Additionally, there’s the provenance angle. An NFT that matches a physical object, like Rare Sams, act as a certificates of authenticity by default, then can trace changes in ownership over time. They can’t be faked or spoofed.

After the initial sale, the provenance of Rare Sams can be traced from being minted in my own Ethereum wallet, to a wallet controlled by the owner of the physical drawing, proving that they got it directly from me, David Z. Morris, the creator. This data will be publicly viewable in perpetuity, and future hypothetical buyers of the drawings can take receipt of the NFTs themselves, creating a time-stamped a digital chain of provenance that could, hypothetically, stretch decades or more.

I largely found myself thinking of these sales, then, more as using blockchain systems to auction off the drawings, rather than selling NFTs with accompanying drawings.

Steps

Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how to create NFTs. Read on for more detail.

Create Images

Install Metamask or other Wallet

Fund your Wallet (About $100 of ETH or less, depending)

Mint to Ethereum with Manifold

Promote it somehow!

List on OpenSea

Create Images: This part is no different from creating any other kind of digital image. I scanned in my sketches, then used the free image editor GIMP to sharpen the sketches and, in some cases, reduce the notebook lines. I kept it pretty simple, because these are just representations of the sketches. But a more ambitious and digital-first project will probably want to hire a specialist for this stage.

Install Metamask: You’ll need an Ethereum wallet installed to interact with both Manifold and OpenSea, and to receive the proceeds of sales. I won’t go into this in detail here, except to emphasize that you should keep meticulous and secure offline records of your private key. Lose that, and you’re fully borked. Metamask is not perfect – see below for a small gripe – but it’s the most trustworthy wallet around. You can install it here.

Fund your Wallet: Be prepared to pay around $5USD to mint each of your NFTs, and another $5 to list them (note these fees do change over time). The easiest way to do this, at least for Americans, is to open an account on Coinbase, buy some ETH, and send it to yourself in Metamask. You can directly copy-paste your public address from the wallet and plug it into Conibase’s “Send” feature. It’s super simple, just be very careful to get the address right.

Mint with Manifold: Manifold.xyz is a fantastic tool for minting NFTs – I can’t recommend it enough. It takes no more than very basic tech understanding to figure out, even if you’ve never done anything in crypto before. Best of all, it’s *free,* though you do have to pay minting fees (again, see below for detailed cost breakdown).

(Mint On Ethereum): You may notice people talking about NFTs on Solana, or even “NFTs on Bitcoin.” Basically, many different blockchains can store NFTs now, and for advanced users, there’s a real question of where it’s best to start - see “Costs” below. But the simple answer is, especially if you’re selling something unique or in small numbers, mint on Ethereum. It’s more expensive, but it’s the main platform for NFTs, and more importantly, the most future-proof.

Promote it Somehow: This one I’ll have to leave to your imagination – you want to get the word out about your sale, and that’s going to entirely depend on your existing network and skills. Meanwhile, If there’s one thing I am not good at, it’s marketing and promotions. And my stature is in itself pretty minor, however highly you savvy few regard me. So someone with more of either or both of those could almost certainly outstrip what I’ve got going here.

My one serious recommendation here is to NOT give any money to the many Twitter accounts that promise to promote your NFT sale. I’m sure some are legitimate, but most are either overpromising what amounts to posting to an account with a lot of fake followers, or they’re outright scams that provide no real value at all. And it’s nearly impossible to tell.

List on OpenSea (or Blur): OpenSea and Blur are the two big NFT auction/sales platforms. I had a hard time deciding between them, but ultimately went with OpenSea. Frankly, I would probably switch to Blur in the future. OpenSea doesn’t have very good UX and in my experience leaves sellers vulnerable to potentially costly mistakes – see below for details.

Another choice is whether to do an auction or a fixed-price sale. While auctions on Ethereum are a bit weird (again, see below for some hurdles I faced), they’re generally better for unique items, while fixed-price auctions may be best for larger editions.

Note that not much is happening “on” OpenSea when you sell through them. The site is largely a graphical front-end to a set of smart contracts, and every transaction reflected on its pages is actually happening on one or another blockchain protocol. You can verify this, with fairly little technical skill, by using third-party blockchain browser like Etherscan. This is totally independent operation from OpenSea, or any other blockchain front-end, which just facilitates you accessing the infrastructure.

Costs

I mentioned above that I sold six sketches/NFTs for roughly $850 total. But there were costs associated with the sale, both on-chain and off, and those bring down my net earnings a good bit.

First, there are on-chain fees associated with minting NFTs. These include Ethereum transactions to create the tokens, and the cost of paying for long-term data storage to keep the images live on Arweave. As I mentioned, Manifold takes care of the Arweave storage and fees seamlessly in the minting process.

It’s important to note that both minting and auction fees would have been much, much lower if I had used a so-called “Layer 2” for my NFTs, rather than minting directly to Ethereum’s base-layer “mainnet.” Minting to an L2 can be useful for some kinds of NFTs, but for 1 of 1 editions and anything truly archival, collectable, or “fine,” Ethereum itself is the best choice. And thanks in part to some technical advances, Ethereum fees are all a lot lower than they were two or three years ago.

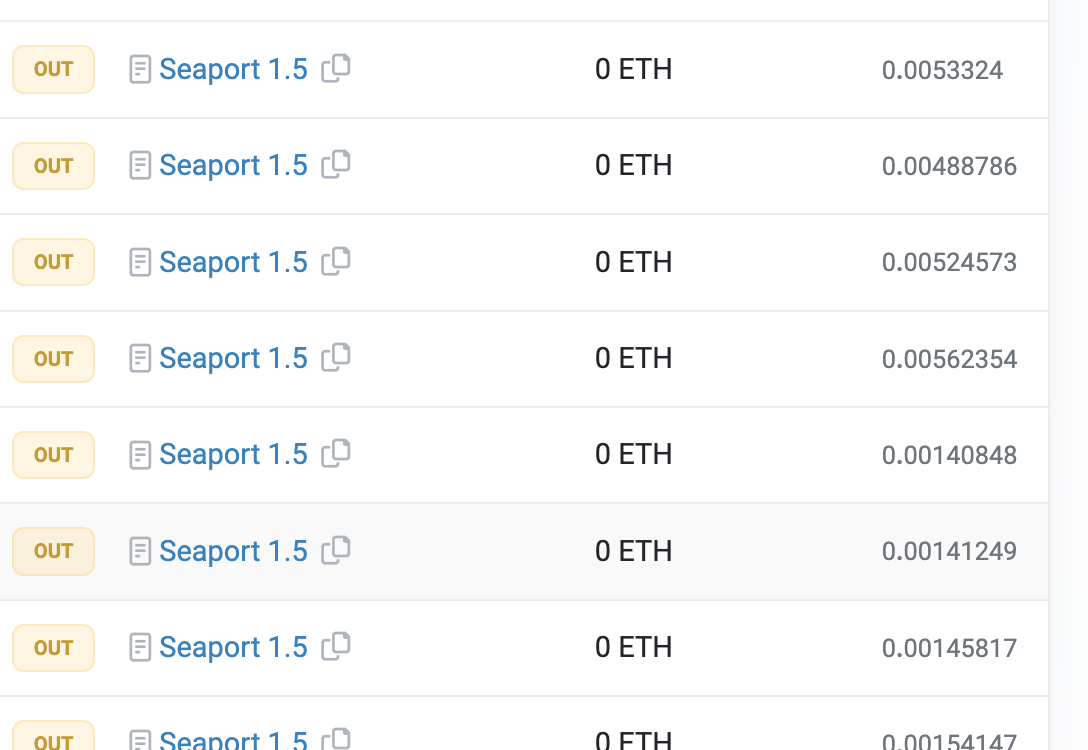

Here are the four transactions that made up the batch-minting process through manifold. The total cost was .027 ETH, or roughly $60 USD as of December 2023.

You’ll see “0 ETH” in the middle column, as these transactions didn’t involve directly sending money. The relevant number, instead, is the smaller grey transaction fee on the right rail, also denominated in ETH.

And here’s a sample of the auction transactions on OpenSea. The total cost of the auctions was, again, around $60 USD.

So that’s $120 in cost to mint and auction the NFTs for $850 in revenue, or a total take rate of about 14%. That’s about the same as eBay’s 13.25% fee for most auctions – but I still have nine of the NFTs, so blockchain wins by a hair.

However, I’m not quite done yet.

I also spent about $30 on some basic frames for the sketches. Then there was the shock of shipping costs. Of the many mistakes I made in this process, it’s ironic that the biggest one had nothing to do with blockchains or NFTs, but instead with the physical mail. That mail system has changed a lot in recent years, and not for the better.

When planning the auction, I assumed the cost to ship a framed image in a flat box would be trivial, in the range of ten dollars. But the real costs wound up being three times higher than that. For international buyers, I had to ask them to cover shipping costs, which I hadn’t stated up front. I hated having to change things up like that, though luckily my buyers were very understanding and generous.

But all in all, shipping wound up costing about $120.

So total costs looked something like this:

Manifold Minting: $60

OpenSea Auction Fees: $60

Frames: $30

Shipping: $120

Total: $270

So, the roughly $850 gross goes down to a little below $500 net.

Is that amazing for the amount of work put in? Not really.

Was it a useful amount of money to be able to bring in at that precise moment? Absolutely.

Would somebody be able to do a lot better with a little more planning and strategy? Again, there’s no question in my mind.

Bonus: If you’ve read this far, and want to talk, I’m offering free speed-consult windows for the next week.

Pitfalls and Shortcomings

While I was really happy with the way the NFT sale went (and continues to go), the process also showed me a lot of problems with various aspects of the process – though mostly with OpenSea.

(The following is pretty granular, so feel free to peace out if you don’t actually plan to use these tools.)

OpenSea is Confusing and Janky

My experience using Manifold was nearly flawless, and I don’t think I’ll be shopping for another NFT minting platform in the future. I can’t say the same for auctions, though: OpenSea’s interface and user experience were confusing, in one case leading to a small loss of funds, and in another case putting me at risk of a much larger loss.

All in all, while OpenSea is still fairly accessible on the front end, the details down the line are frequently pretty shoddy, so it’s no surprise Blur has gotten so much traction as a potential successor.

Auction vs. Fixed Price: When I first listed all 15 Rare Sams, I accidentally listed them as “fixed price” sales at 0.03 ETH, instead of 30-day auctions starting at 0.03 ETH. When I went back to fix the issue, I realized that the problem was that crucial information about auction vs. fixed price sales was left “below the fold” on a couple of interaction panels, simply making it unclear what was going on.

Again, I’m stupid, inattentive, and lazy. But that’s the user you should design for when people’s money is on the line: It simply shouldn’t be possible for a even a barely-attentive human being to overlook such a crucial distinction.

As it happened, I had two extremely eagle-eyed buyers who snapped up Sams at what was supposed to be the *starting* auction price rather than the final sale price. In the end, I didn’t actually mind that much – maybe in theory I lost a few bucks that these NFTs might have been bid up, but on the other hand, I got quick sales on the board, and the snipers wound up being fans who were paying close attention and got rewarded.

Worse yet, this listing error happened *again* when I listed the items again. I also somehow managed to set a “floor price” for the collection without even noticing I’d done that? It cost me ten bucks to reverse one of these mistaken listings, and would have cost me more like $40 to revert all of them, but I decided to leave a couple at a fixed price … sigh.

Manual Auction Closeouts: I also experienced a strange problem with OpenSea: Perhaps thanks to the way blockchains work, an “auction” on OpenSea is not like an auction on eBay, in one extremely important way: auctions do not close automatically. You have to manually accept the highest offer (presumably). This can be a problem if you’re not paying attention, because these “offers” have expiration dates. If you don’t accept an offer in time, nothing happens – even though you’re trying to sell something and the bidder has offered to buy it. Frankly, it’s pretty silly.

Buyer Messaging: I may just be an idiot – in fact, I’m pretty sure I am. But as an idiot, I couldn’t figure out how to message my buyers within OpenSea. Luckily, I was able to figure out who most of them were indirectly and get in touch via Twitter and the like – but this is, again, simply an absurd omission.

“Sales” that weren’t “sales”: This is a minor gripe, but it speaks to the general imprecision of OpenSea’s UX. The below screenshot is a detail pane of one of the Rare Sam NFTs, and by looking at it you might think that it “sold” for 0.033 ETH.

But in fact, this one didn’t sell. It was simply listed at a total of .033 ETH – a total that weirdly seems to include buyer fees?

This pile of jank raised $300 million dollars in 2022, and while I know things have been difficult in NFT land, maybe OpenSea could have used some of that money to … make its site better? Call me crazy.

Metamask and “Internal Transactions.”

So yeah, OpenSea is pretty whack, but it didn’t create every moment of confusion and anxiety. (Dealing with blockchains is largely just a series of small panic attacks when you suspect you’ve just fucked up and lost everything.)

Another big one nearly came for me as my auctions were starting to close. It seemed like my Metamask wallet had the right amount of money in it – but I didn’t see incoming payments matching the auction sales. Foolishly, I hadn’t kept close track of my spending in the blur of minting and auctioning, so there was a shadow of doubt that some money had gone missing.

But in fact, the issue is with Metamask, and it’s very stupid. Basically, if you’re auctioning NFTs you minted from the mint wallet, auction payments coming back from OpenSea will be considered “internal transactions.” These will show up on Etherscan under an “internal transactions” tab, but Metamask simply *doesn’t display them at all.*

I’m sure there’s some sort of technical rationalization for this, or some power-user utility. But let’s be blunt – it’s dumb as hell. No “real world” user is going to understand or care about the technical reason a payment from a stranger is considered an “internal transaction.” They’re just going to get freaked out like I did, and blame the bad experience on either MetaMask, OpenSea, or “crypto” at large. This issue truly, badly needs to be addressed by the MetaMask team, in some way or another.