How to Read With a Pencil: Resurrecting Focus With a Research Agenda

The most fun part of writing a book? Buying other books.

Happy Sunday, readers – including many new paid and free subscribers over the past month. Today, we’re again talking about how to read, write, and think more clearly in the wake of the pandemic’s mind-melting impacts.

The following post is paywalled, as are most Sunday posts. Those are primarily posts about Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX, and the process of writing my book about them.

As thanks to all new subscribers, of whichever sort, I’ve unlocked the January post The Theory and Practice of Raising a Criminal Child. It’s a deep dive into Barbara Fried’s determinist arguments that, in essence, there is no such thing as moral culpability – an argument she spent decades making before her own son was revealed as a criminal of historic proportions.

Enjoy, and consider becoming a premium subscriber to get these posts as soon as they’re released.

Back when this newsletter was just a fun little sideline, I published a post titled “Towards a Program for the Resurrection of Focus,” which proved relatively popular. As I wrote at the time, pandemic lockdowns (and some other factors) had left my brain an addled mess, and I was getting tired of it. It seems I was not alone – a lot of people are hoping to reclaim center, focus, and depth in their intellectual lives.

My own lost focus centered around reading and books, and the importance of those has only been reaffirmed since: in case you missed it, Sam Bankman-Fried hated reading books. One way of interpreting his incredibly stupid actions is that he had never trained his brain to think in the kind of big-picture, multivariate, nuanced way that comes with reading at length. History seems to suggest that it’s very hard to be a robust thinker, or even a particularly antifragile human being, if you’re not at least occasionally really doing The Big Work.

Hence my recent anxiety over lacking a single big, overarching intellectual project. Getting back to that is a huge unlock for the simpler agenda of Reading More, most of all because it refines motivation to a single guiding question that you want to answer. Maybe your goal is to write a book, or just an article or blog post, or maybe your motive is something entirely different. But whatever the purpose of your research program, having a purpose provides both a clear reason to read a particular book – and, perhaps equally important over time, a reason not to read things that aren’t on the roadmap. Exclusion, after all, is implied by the literal definition of ‘focus.’

I know the dynamic well because during and for many years after my PhD program, I was almost constantly researching one big topic or another, such as the history of sonic competition for my work on car audio (recently featured by JSTOR); or the complexities of Japanese nationalism for my dissertation. To have this sort of research agenda, as I’ll get into below, is to be on a wandering journey with no set destination, or even necessarily a timeline. It is a mystery to be solved, rather than a series of boxes to be checked, and in theory, it can go on forever. It has to be approached with a childlike hunger and naivete, because you have to always be open to novelty.

I’ve begrudgingly come to understand that the constant, emergency-room rhythm of journalism wore away at my ability to leave space for that kind of journey. And since stepping away from the professional newsroom, I’ve been thrilled to find the Big Work coming back into my days. Here’s what that looks like at the moment:

Research in Motion

There’s a lot to be written about how to find a research project, which is arguably the hard part of all of this. It involves, above all, finding questions that you can’t answer, but which keep your attention. For me, these specifically tend to be questions about human nature and motivation. Often, the best research question can be phrased in very simple terms. In the case of Sam Bankman-Fried, my question boils down to some refinement of “what the hell were these people thinking?”, in the fairly literal sense that it’s a book about philosophy and ethics.

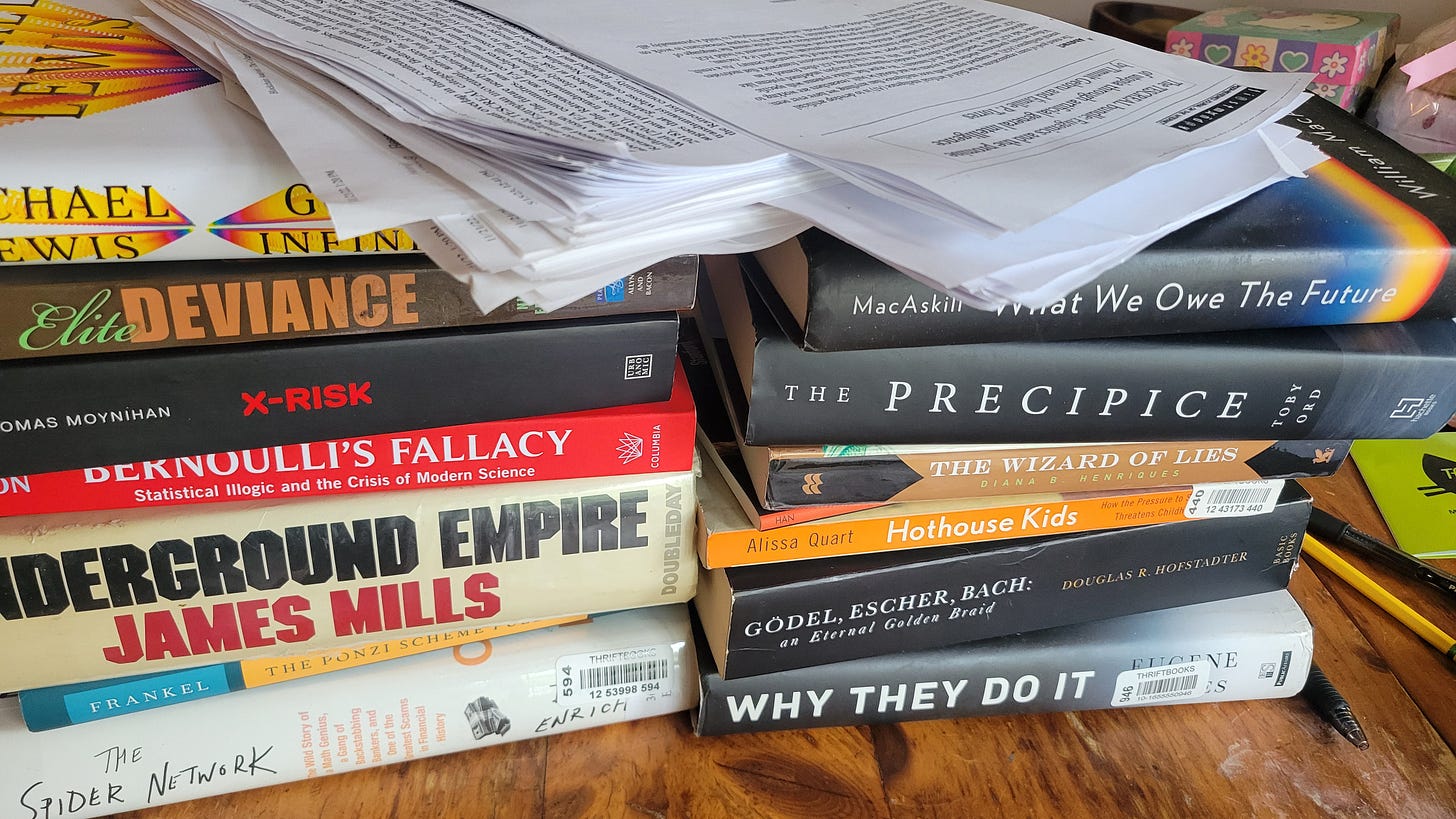

But my focus here is on practical tips for major research. And I’ll walk you through some of my own fat stack of sources so far, to give you some sense of how ideas interlink and support each other – what I’m provisionally referring to here as the “spiderweb” nature of knowledge creation.

Below, we get into:

Finding Credible Sources

The Importance of Physical Media

Sourcing via the Spiderweb

Reading as “Thinking With” the Author

So yeah, here we go.

How to Find Credible Sources

It has become much more widely accepted over the past year or two that the internet is a fucking garbage fire, and you should approach any research project with that assumption front and center. Which is to say, trying to do serious research on the Internet will only get you a very short distance before you hit a wall – or worse, get diverted down a misleading rabbit hole. Believe it or not, a lot of real information isn’t on the internet in any form, and as bad information proliferates, what good there is becomes harder and harder to find.

That’s just one reason that, perhaps especially for those without formal postsecondary research training, I recommend starting with books as research pillars. Books with all the standard signals of legitimacy – big publishing houses and traditionally-credentialed authors, whether prestige journalists or significant academics. That’s partly for the trustworthiness and balance of the information within, but almost as much for the rigorous sourcing that comes with a serious book. You’re going to need to draw on footnotes and the like to continue on this journey, so a book without proper sourcing is of very limited utility.

This is also why, if you have the resources, I strongly recommend buying your own copies of research volumes. I recommend this for two reasons: so you can keep them on hand without worrying about, say, a library deadline looming; and so you can write in them, on which more below. Usually this isn’t too expensive, at least at the outset, when you’re mostly dealing with mass-market products that can be easily found used. Most of the books in my stack above were less than ten dollars.

There is another option, which is looking for academic papers through a database like JSTOR.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dark Markets to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.