Nothing is True, Everything is Exchangeable

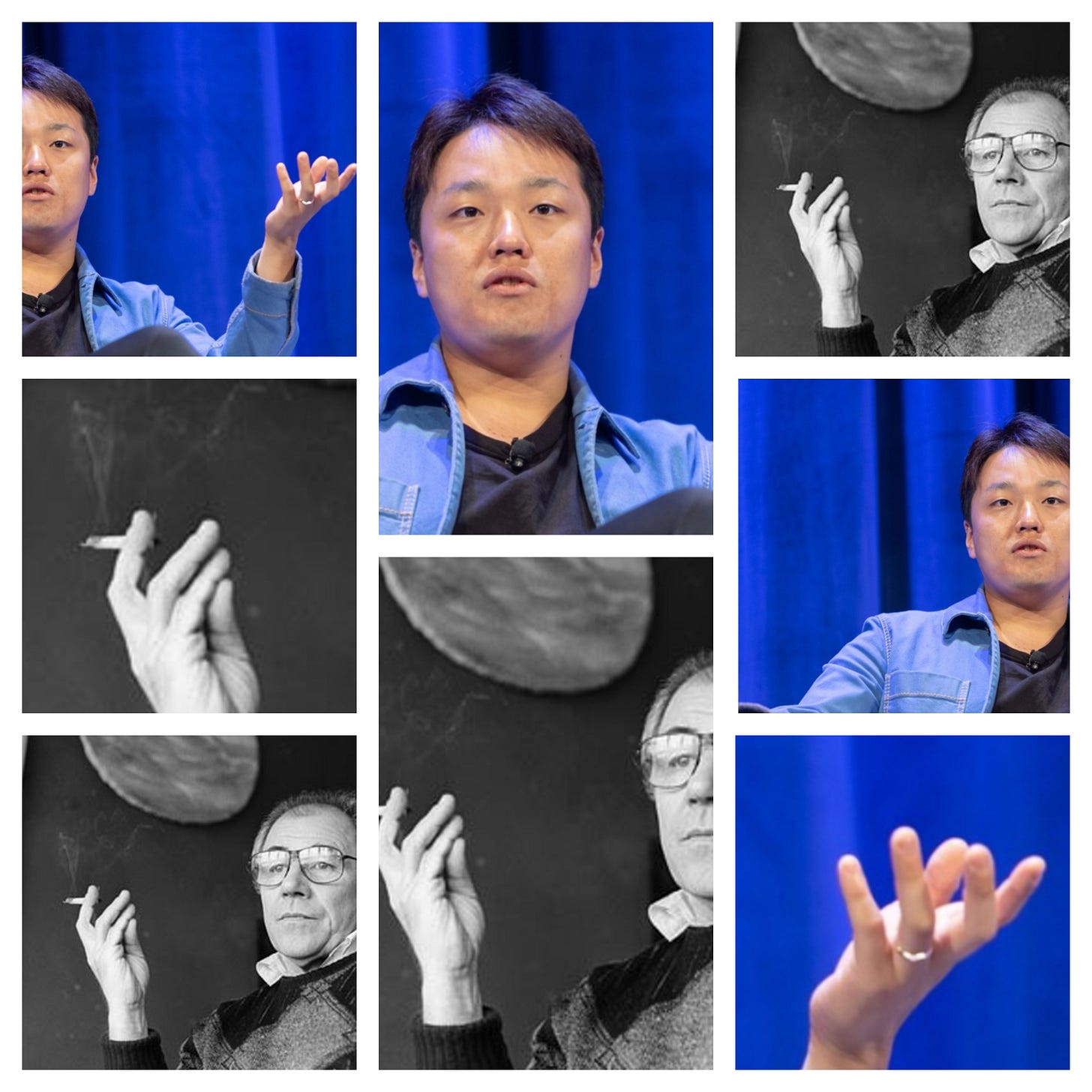

Do Kwon, UST, and the Simulacra of Production

Most of you likely know that last week saw the spectacular collapse of a large blockchain project, with the Terra system collapsing from a paper value of $68 billion dollars to zero practically overnight. In my daytime capacity as someone with actually useful knowledge, I’ve been diving into the economic details of the system, why it unwound, and the suffering that has ensued.

In fact, in one of those strokes of luck or inspiration that you get maybe twice in a journalistic career, I managed to effectively predict the collapse in real time. A little over a month ago, when Terra surpassed one of its competitor systems, we assembled a strike team over at CoinDesk and started pulling threads. In the piece I wrote, I described the exact worries that wound up proving very well founded just three weeks later. My colleagues also did some dynamite work. It’s an odd circumstance for celebration, but I know I saved at least a few people’s money, so I’m frankly kinda feeling myself right now.

The timing is fortunate for another reason. Along with a group of other mostly crypto-industry friends, I’ve been working my way very slowly through Jean Baudrillard’s Symbolic Exchange and Death, a book that will rapidly expand how you think about money and the economy. If you’re interested in joining this group, the Money and Death Book Club, we have a nascent but growing Discord here. (If this invitation expires, feel free to reach out on Twitter for another.)

As you might guess, the book is a tough journey, and I’m far from finishing myself. Luckily Baudrillard gets right into explaining his core concept, and it’s just delectably applicable to this whole Luna situation. Baudrillard is not widely described as an economic thinker, of course (and I’d never tar his good name with “economist”) – rather, he’s best known for a loose association with the Matrix films, with the vague ideas of simulacra and simulation, the anxiety that we’re not quite living in the real world anymore.

Money for Nothing

Even at that superficial level, the story of Terra and its creator, Do Kwon, exemplify the basic gist. Kwon created digital money out of nothing, an entire system of value referring only to itself, Baron Munchausen pulling himself out of the mud by his own hair. Bitcoin is a vision of a possible future: Luna was The Matrix striving to become real dollars today.

In very broad terms, Terra was a “stablecoin” intended to be worth $1 at all times. To accomplish this, Kwon created another token, called Luna, that could be profitably arbitraged against the TerraUSD token whenever it wasn’t trading at exactly $1. The market, following those incentives, would keep TerraUSD balanced at $1.

Actually that wasn’t such a broad description. That’s really the whole thing. If you have the odd feeling something’s missing, it’s because the entire idea is fucking moronic on its face – a financial perpetual motion machine whipped together by the dumbest illusionist of the Earth’s dying cultures. I’ve been writing critically about similar schemes on a smaller scale for at least three or four years now. Many have already failed.

They return, tasking me as the white whale tasked Ahab. They all die.

Yet this idea attracted a substantial amount of capital from serious investors, as well as a tragic number of clueless financial novices. It is a hugely embarrassing moment for a lot of people with a lot of money – as well as a scary one for lots of people out in the real world. A lot of people got tricked, I’m saying, at all levels of supposed professional grounding, into buying a metric fuckton of electromagic beans.

An absolutely key element here is that for a little while – six months to a year, maybe – these things were worth a lot of money, on paper and frequently in practice. And then, incredibly quickly, they were worth nothing. It was all very manifestly some sort of mass hallucination – how could it be possible that real value would simply vaporize into nothing?

In this case the literal answer is that the mechanism design was so bad that the token was essentially designed to fail. But the overextension of valuations, as we’re seeing right now, is total – Netflix, Tesla, presumably real estate soon enough, redux.

It is the function of finance to logically and reliably join the present and the future, but the future implied by finance keeps getting delayed – self-driving cars, freedom from the cable company, a totally sound electronic dollar backed by nothing. Each deferral of the future triggers the deflation of a bubble.

All of this gets us to a much more rigorous sense of what Baudrillard actually meant when he wrote about simulacra and simulation. It’s simplistic to read them as merely commenting on the proliferation of representations and communication in our lived experience, the electronic always on-ness that has returned to haunt pitches for various takes on “the metaverse.” This is the version of Baudrillard that third-rate intellects might trot out to impress a girl during a conversation about The Matrix.

But simulacra and simulation are not just matters of media ecology. They’re also a post-Marxist structural economic analysis.

The Economics of Illusion and the Illusion of Economics

“The reality principle corresponded to a certain stage of the law of value. Today the whole system is swamped by indeterminacy, and every reality is absorbed by the hyperreality of the code and simulation,” he writes in a summation we again can’t help but read as a description of our present. “We don’t make things in America anymore,” we moan, and it was predicted by this guy in France in the seventies. Instead, we trade symbols, we speculate, we worry about venture capital returns.

And while the spectacular collapses of leveraged hallucinations make headlines, the ability of finance to draw future value into the present and consume it here – for a little while – has created all manner of zombie entities, things like Uber, which insisted for a while that its bad economics were just a prelude to self-driving cars, but recently divested that unit, since we are beginning to figure out that self-driving cars are much, much harder to pull off than we quite realized. Yet they soldier on, absent premises unremarked on.

The future came and went and was never delivered, yet somehow a fifty billion dollar (I had to look that up and, really, Jesus Christ) company still exists. That’s because a “company” is no longer a collection of assets and designs and people, but instead a set of ideas about production or logistics and how to rearrange it, and a set of projections about how much that idea is worth if copied worldwide like software. Like Populous or SimCity. All of this delivered with numerical precision and an entirely straight face to investors.

And here is Baudrillard: “Political economy is thus assured a second life, an eternity, within the confines of an apparatus in which it has lost all its strict determinacy, but maintains an effective presence as a system of reference for simulation.”

This gibberish is another way of saying that economics, measures, and projections were powerful efficiencies in the industrial era when they tracked commodity and production flows. Now, these projections take on a life of their own, as processes, as stories, even forming a kind of proof-of-work algorithm within the financial system by which third-party analysts expend hours evaluating the reasonableness of other adults’ merely optimistic or entirely delusional mathematical fantasies. That’s the real work that secures the value of the stock. That and journalism, I suppose.

Games of the Future

A simulation doesn’t just mean a virtual reality game. A financial projection is also a simulation. It is in a sense literally a game – like Populous or SimCity, a financial projection has parameters and interactions meant to reflect and abstract the messiness of reality itself. But none of these are particularly realistic games, in the grand scheme of things – including finance.

That pesky underlying existential indeterminacy might not be the biggest factor that makes investing resemble gambling, but it’s pretty far up there. We can’t know the future, and finance attempts to. Financialization continues apace in its penetration at every level, and it’s unclear whether we can get better at predicting before our entire society rides on the flip of a random number generator in some guy’s garage.

But no, the real beam in the eye of such simulations is this: The promise of a predictable outcome, the security implied so reassuringly by numbers and formulas, generates its own countervailing risk. The complacency of the econometric mind structurally incentivizes overinvestment, overspeculation, overleveraging. These risks and bets pile on top of one another, plug in, share blood, recursively and incestuously, on spreadsheets on mainframes around the world.

And what is cryptocurrency at its worst but a playground of the purely econometric, purely SimCity-minded? How much more purely can it extend econometric reason unfettered from any troublesome social reality – all the quicker to show some adventurers, at least, how little mercy there is out there in reality? And thank god for that – the reality principle rearing its ugly head with such tenacity, for all the economists’ persistence.

A Trading Floor In Every Cook Pot

“The current phase, where ‘the process of capital itself ceases to be the process of production’, is simultaneously the phase of the disappearance of the factory: society as a whole takes on the appearance of a factory.”

As is often the case in this book, it’s hard to imagine what Baudrillard had in mind in 1978, mostly because he seems to be describing our own situation half a century later. We constantly bemoan the expansion of work out into our everyday life, its fracturing into hypermanaged commodified moments, and the inverse commodification of our ‘play’ into a corporation’s saleable product via the tentacles of social media.

A cryptocurrency like Luna represents not the dispersion of the factory into society as a whole, but the fragmenting and dispersion of the finance industry built on top of the factory out into society. But the factory’s gone, and left to itself, the ghostly simulacra of finance has burrowed deeper and deeper into our collective consciousness, to the point that average people felt it was normal to put their life savings into cryptocurrency. This is the dominating second life of political economy.

One of my neighbors, from what little I can infer as I avoid him, seems to be some kind of day-trader. I have watched his health and mental state decline over the past few weeks along with the crypto market. He’s suffering the agonies of a blown-up hedge fund manager, sweating every tick of the candle day in day out. He’s a shadow of a man, unshaven, wearing pajamas in the hallway. But he’s not getting two percent on two billion – he's doing all this with his own money, and when he loses, he loses everything. All ten grand of it, if I had to guess.

He is not a day trader, he is a victim of the finance industry’s occupation of our collective dreamworld.

Under these circumstances, two things are destined to be true: First, that some people, poorly trained and inexperienced, will truly believe nonsensical things about finance. And second, that some people will believe those people, and commit money to those nonsensical ideas. And because our entire economy is in the form of a vast series or network of simulacra, these commitments will have real consequences when they fail.

Is that fraud, or is that just being a fish in the great financial school? We read each other’s flashing dorsal scales, and what we read are stories of the future, and which direction to swim.

Let us pray we follow friends.