Techno-Rationalism and the Denial of Death

There's a dark secret at the root of Effective Altruism and related ideas. Also: a new forum for supporters.

Happy Sunday, and welcome to Dark Markets. As you may have heard, I now have a contract for the Sam Bankman-Fried book.

This is a book with a minimal advance (basically a symbolic courtesy), which anyway only comes when the manuscript is delivered. So your support remains essential - and not just financially. Supporting members will now get access to The Money and Death Social Club, a Discord server for discussing the ideas behind the book, reading related work, and generally connecting over a shared interest in deep analysis of financial fraud and tech hype.

A link to the M&D server is behind the paywall below. I hope you’ll join us. (Please note that if you use a trial subscription to access the link, you will only have server access for the length of your trial.)

Today’s entry is fairly significant. Over the past two years, I’ve puzzled over a core mystery of Sam Bankman-Fried: his seemingly complete state of denial over the reality of his own actions. The answer I’ve arrived at involves the opposition between two worldviews: one that acknowledges the unknowability of both human motivation and the universe, and one that insists on the knowability and predictability of both.

In essence, the core moral failing of SBF and his allies is the same as their core intellectual failing: an inability to reckon with the contingent nature of human existence, and ultimately, with the inevitability of death.

One last treat for everyone: I’ll also continue to use this newsletter to talk about the writing and research process, hopefully in a way that’s helpful to subscribers on their own projects. One challenge of this project is that it brings together a massive number of threads from philosophy and real life, which relate to each other in complex ways.

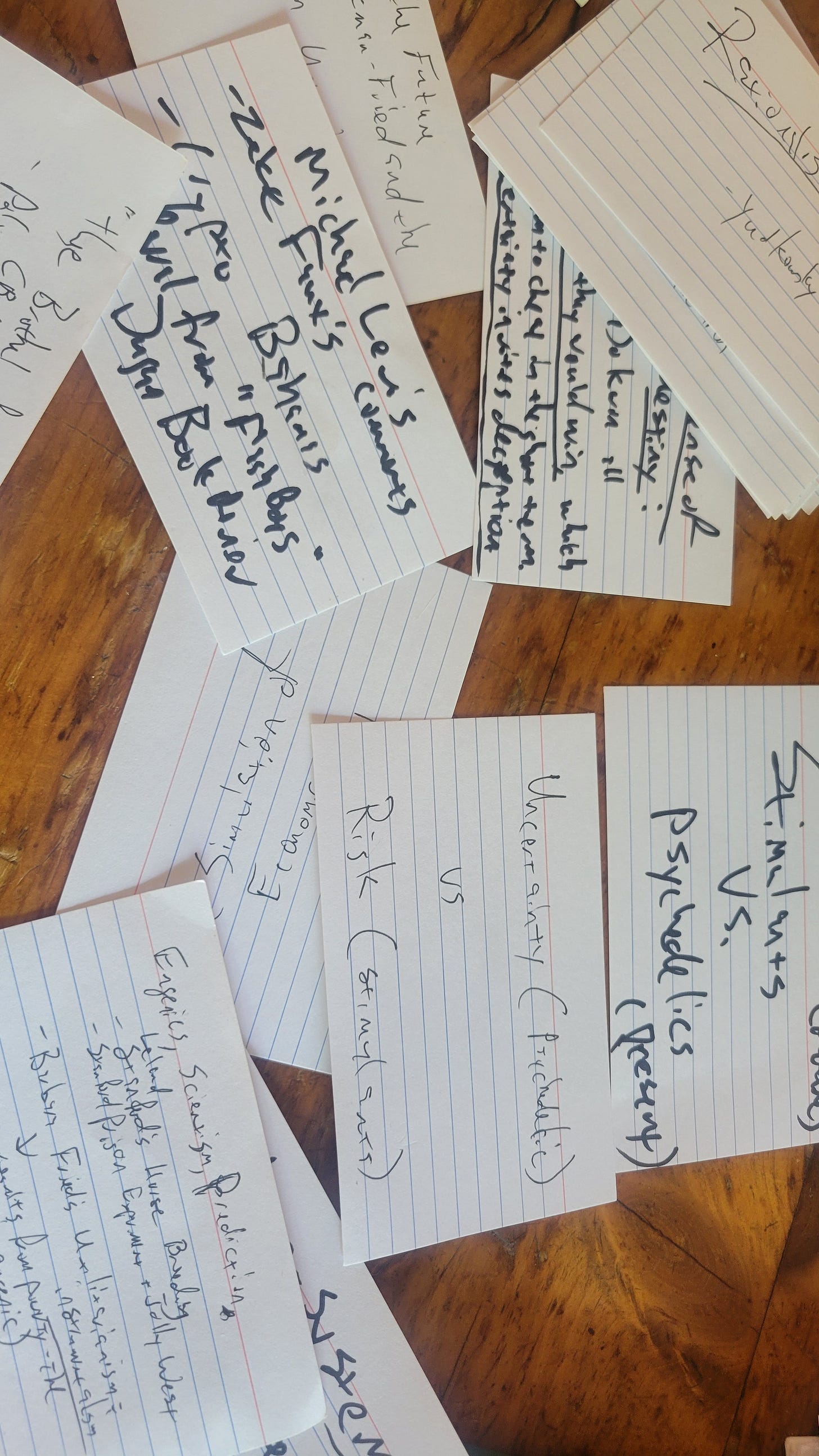

Here, at least for now, is my approach to that challenge: Index cards.

The concepts, facts, and etc. recorded here are the basic building blocks of the book. Soon I’ll start arranging them, probably in a Charlie Kelly-style pinboard, as a way of outlining. Until then, they’re accumulating, willy-nilly, in a little box on my desk.

The chunk on stimulants is going to be very fun.

Effective Altruism and the Denial of Death

As I’ve mentioned before, I didn’t particularly follow Sam Bankman-Fried’s trajectory in the years of his ascent, mostly because for those of us serious about the decentralized technology and cypherpunk ethos of cryptocurrency, a centralized exchange operator is perhaps the least interesting person still nominally within the industry.

And of course, Sam was fairly open about not really caring much about crypto per se, instead having seen it merely as a good opportunity to make money - his open cynicism about this was, as Matt Levine has written, a perversely reassuring signal to members of the public who already (mistakenly) viewed crypto as nothing but a scam. That probably included many policymakers on Capitol Hill - but I digress, a privilege I reserve for myself in these dilatory sketches.

Even after his downfall, Sam wasn’t immediately all that interesting. For technical reasons relating to their distance from the center of the crypto ethos, centralized exchanges fail all the time, and those failures are usually boring thefts or hacks whose perpetrators disappear (for as long as they can). At best, they’re pedestrian mysteries like the disappearance of QuadrigaCX head Gerald Cotten. Sam was, in other words, a dime-a-dozen rug-pull artist … until he started talking.

Because the most interesting thing about Sam Bankman-Fried was always his denials. We now know that many of these were strategic lies - for instance, based on Can Sun’s testimony, we know that Sam’s argument that the missing funds were the result of margin lending losses [https://protos.com/sam-bankman-fried-lied-to-ftx-lawyers-about-using-customer-funds/] was based on a “hypothetical” but untrue scenario laid out for him by Sun.

More broadly, though, Sam’s lies seemed far less strategic than they were compulsive, which became most clear when he took the stand in his own defense and repeatedly perjured himself. At this and other moments, he seemed to genuinely believe his own lies. In everyday terms, we could call this compulsive self-deception “delusion,” or as I’ve become increasingly convinced, “sociopathy.”

More fundamentally, though, it suggests that Sam must be understood in terms of depth psychology, a.k.a. psychoanalysis. At the broadest level, psychoanalysis is the idea that “we know not what we do” - that humans are driven by anxieties, traumas, and animal instincts that don’t surface in the conscious mind.

But the goal of this book isn’t primarily to psychoanalyze Sam Bankman-Fried - it’s to understand the ideas and organizations that smoothed his commission of one of the biggest financial crimes ever. And those ideas - the related cluster of techno-utopian concepts including Effective Altruism, Longtermism, and Transhumanism – reveal themselves to be projects of self-delusion and psychic repression.

Specifically, there is a staggering volume of evidence that this “TESCREAL bundle” serves to comfort believers in the face of an unpredictable universe, their own inevitable death, and the ephemerality of the human species itself.

My starting place for coming to grips with the techno-utopians’ specific psycho-pathological ideological situation is Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, a Pulitzer-prize winning and best-selling psychoanalytic treatise published in 1974. One passage in particular I feel explains much of the Sam Bankman-Fried phenomenon, and of the techno-utopians in general:

“If we had to offer the briefest explanation of all the evil that men have wreaked upon themselves and upon their world since the beginnings of time right up until tomorrow, it would be not in terms of man’s animal heredity, his instincts and his evolution; it would be simply in the toll that his pretense of sanity takes, as he tries to deny his true condition.”

Here, we can substitute “rationality” for “sanity.” The goal of the techno-utopians is ultimately a completely controlled and rational view of the universe. But by denying and supressing the irrational, and most of all by then assuming that the world is predictable, they lead themselves into crimes and misdemeanors of which the collapse of FTX is only the most spectacular, and by no means the most damaging.

Rebuilding God

Perhaps the single most revealing clue to this reading of techno-utopianism as a form of psychic repression lies in the work of Ray Kurzweil. Kurzweil’s prediction of “the singularity,” a moment of magical convergence when machines become intelligent, is a fundamental building block in the worldview of most living techno-utopians. That’s most obvious in the “Rationalists”, Longtermists, and EAs focused on the “extinction risk” of a supposedly looming “AI Apocalypse.”

But Kurzweil wore the emotional motives for his theory on his sleeve. A corrolary to “the singularity” is the idea that human beings will be able to upload their consciousness into computers. He has written repeatedly that he hopes for this outcome specifically because he misses his own deceased loved ones. Kurzweil even went so far as to create and use a chatbot based on the writings of his dead father, Fred. Kurzweil’s daughter (Fred’s Grandaughter) wrote a graphic novel about the experience, which I’ll have to check out.

That’s arguably ghoulish, but it’s also very understandable. Losing people is hard. Even from the most skeptical perspective, Kurzweil’s delusional desire to “resurrect” the dead invites empathy more than condescension.

More generally (as I recently discussed with Dr. Emille Torres in a podcast episode you’ll get soon), the Transhumanist and Cosmist belief systems posit a kind of “digital heaven” of many consciousnesses. That’s not just uploaded versions of living people, but even new “people” who are entirely digital.

Moreover, the Rationalist canard of “Roko’s Basilisk,” which imagines a future AI punishing humans who are skeptical of it, implies a vision of Hell – a condemnation to remain in your feeble human body when everyone else is being digitized. Dr. Torres sees all of this as an eschatology – a theory of the end of the world. Those who are righteous will be sent up to digital heaven, while the unbelievers will suffer in the hell of the physical world.

Finally and most revealingly, many engineers involved in the quest for “artificial general intelligence,” or human-like thinking machines, sincerely believe they are in the business of what some call “divinity engineering,” or literally building God. Even those who don’t use quite this language invoke the hypothetical God-like powers of AGI, particularly its purported capacity to come up with completely effective solutions to all of humanity’s problems.

(This, by the way, is apparently why many Longtermists, including Sam Bankman-Fried, have seemed largely unconcerned by climate change: they believe that we can build an AGI that will solve that problem, so the only ‘real’ problem becomes controlling the AGI.)

Prediction, Control, and the Unconscious

The other angle for a psychoanalytic understanding of techno-utopianism has to do with their blanket insistence on the predictability of the future. It’s a core tenet of Longtermism, even though it is largely a delusion - even EA leader Toby Ord admits in his book that the compounding rate of error in forward-looking prediction renders things like calculating the odds of the Earth getting hit by an asteroid little better than pure than speculation.

(More broadly, I have a lot more work to do to understand broad critiques of the entire structure of AI modelling as a predictive tool based on historical data. There is a significant debate in mathematics over the deep validity of inferential modeling.)

Ord barrels right past this seemingly fatal objection to the entire longtermist project. The entire techno-utopian project, in fact, arguably ignores grounded reason and logic to put forward a series of pseudo-religious premises, which it then re-wraps in the superficial rhetoric of rationality.

Another clear example of this is the mathematizing impulse shown by Bankman-Fried’s constant return to “expected value” calculations. These are common in finance, a relatively bounded problem subject to at least some degree of forecasting - but SBF and the Effective Altruists applied it to any number of unbounded problems. They assigned numerical probabilities for certain outcomes, apparently largely based on instinct, and used those numbers to make many different kinds of decisions.

Numbers, when deployed in this cross-realm and improvisatory way, become little more than totems or fetishes, superficially ‘scientific’ and rational, but in substance, primitive and ritualistic. In fact, they become more dangerous than a primitive ritual because they imply a precision and certainty that isn’t there.

One way to think about this is as the difference between “risk” and “uncertainty.” Sam Bankman-Fried was a compulsive gambler, but he seemed to be operating out of some degree of rationality because of the way he assigned numbers to long-run, unpredictable outcomes. This is a terrible trap to which the scientistic and “rationalist” mind is uniquely subject: there is no such thing as a numerical “probability” when it comes to the truly uncertain.

Assigning odds to the unknown transforms it into the merely risky, subject to probabilities - and thus, not just to financialization, but to wildly overconfident financialization. That’s why Sam could rationalize his borrowing of customer funds - he sincerely believed that he had mastered the chaos of the universe simply by assigning risk probabilities to things. He was so certain of this that he didn’t think failure was a possibility.

Stimulants, Mathematics, and Certainty

“When you combine natural narcissism with the basic need for self-esteem, you create a creature who has to feel himself an object of primary value: first in the universe, representing in himself all of life.”

That passage from very early in Becker’s The Denial of Death absolutely begs to be applied to Sam Bankman-Fried. Bankman-Fried clearly thought of himself through the lens of what Becker calls the “hero-system,” through which accomplishment alone validates the individual’s value, and moreover guarantees a certain kind of immortality through achievement. A system through which, Becker writes with suggestively numerical language, “science, money and goods make man count for more than any other animal.”

The most profound takeaway from Becker for me so far is his argument that this form of heroism is actually the source of human evil, partly because it engenders overconfidence when it comes to meddling in the affairs of society and other humans. Certainly that was true of SBF.

More specifically, Becker argues that children who grow up with supportive parents are most able to push away the fear of death, transmute it into activity, and take control of the world. A person “doesn’t have to have fears when his feet are solidly mired and his life mapped out in a ready-made maze,” Becker writes. “All he has to do is to plunge ahead in a compulsive style of drivenness in “the ways of the world.”

However it might be characterized, Bankman-Fried’s path into finance was certainly no great swerve from the expected path of a person of his background in the early 21st century. In turn, we can see his allergy to deep reflection in his hyperactivity and his and his cohort’s consumption of stimulants (the rejection of boredom is also the rejection of the fear of death).

Hyper-rationality, finance, oddsmaking, and mathematization in general are all related to this. The imposition of rationality over everything amounts to a refusal to grapple with the irrational - including, as Sam found out, the true uncertainty that exists out in the world.

Becker quotes Blaise Pascal’s characterization of this lust for “rationality”: “Men are so necessarily mad that not to be mad would amount to another form of madness.” This would seem to apply particularly to the strain of determinism that SBF got from his mother, Barbara Fried. Barbara does not believe in human free will, ultimately characterizing humans as little more than automatons - a predictability that is necessary to the larger project of making the future predictable, and pushing away the demons of uncertainty.

The Money and Death Social Club

Finally, this is a permanent link to the the Money and Death Discord server, exclusively for Dark Markets premium subscribers and invited VIPs. Please do not distribute this link.

Side note. Again, there are three important points to be verified. A) predictions of sufficient accuracy can be made. B) They can allow for a quantifiable bad behavior. C) That is offset by a quantifiable larger good result.

Per A, I often think about this article https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2024/2/13/24070864/samotsvety-forecasting-superforecasters-tetlock . Notably, it was published as part of Vox's Future Perfect series. Which was given a grant by SBF's foundation (or, effectively, SBF gave away funds that were actually user deposits to Future Pecfect). Vox first wrote they put the project the money was going to go to on "pause" https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23500014/effective-altruism-sam-bankman-fried-ftx-crypto . Then eight days later the Washington Post said Vox planned to return the money https://www.washingtonpost.com/media/2022/12/20/sbf-journalism-grants/ . But if you look at Future Perfect articles, as recently as this year, they still only say the project is on pause or "cancelled," and I can find nothing about actually returning the money https://www.vox.com/business-and-finance/2024/3/28/24114058/sam-bankman-fried-sbf-ftx-conviction-sentence-date .

But, yes, I wonder about these superforecasters https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superforecaster . They, of course, were never consulted by SBF, as far as I know, but perhaps they can give the upper bound of point A. Not sure if we have enough data (time and sample size) and can apply their forecasts to the situations EA utilitarians supposedly calculates for. However, I'd like for someone to try, and then hear the analysis, preferably from someone possibly a bit more impartial than Vox's Future Perfect.

"there is no such thing as a numerical 'probability' when it comes to the truly uncertain."

Not to be pedantic, but that's basically saying math, as most people knows it, doesn't exist. In a purely abstract way, in a binary situation of equal weight outcome, the probability is 50-50. It's an abstract, but abstracts are things by most definitions.

In the non-abstract, one can make an approximate probability, which is still a thing. It is uncertain that a coin flip will be heads or tails. But there is an approximate 50-50 probability on heads or tails.

Now, to be extra pedantic, you could say that knowing the exact probability is unsure. You can't know the number of atoms on the head's side versus the tails' side and whether a butterfly will flap its wings across the planet and affect it's trajectory. You could do all the calculations and measurements humanly possible and come up with odds of 50.001 to 49.999, and it's really 50.0011 to 49.9999.

So, to say in real world scenarios, no one would be able to get exact percentages is fair. But of course that is not controversial. Because to say one can get perfect percentages, such as exactly 75% to occur, of all things would be frankly the same power as saying one could predict exactly 100% to occur of all the things. Both would be infinitely more powerful than normal human ability, and would no doubt allow one to rule the world.

Then you can try "there is no such thing as a numerical 'probability' of sufficient probability when it comes to the truly uncertain."

But of course that's not accurate, or casinos would be out of business. They can control quite a bit of the environment, such that butterfly flaps are unlikely to sway the ball in the roulette wheel. And while they cannot be sure one number slot does not have enough extra atoms to make it slightly wider than the zero slot on the roulette wheel, that extra width is generally not going to be impactful compared to the fact there is that zero slot, giving approximately 2.7% odds advantage over any player (that's the European wheel, American wheels have the double zero also and even better house odds). With sufficient volume, that 2.7% benefit could be at least at whole percentage point off and still be profitable. For the behavior of a casino, the percentages are definitely sufficiently accurate.

So, what I think is being said is:

"there is no such thing as a numerical 'probability' accuracy that can sufficiently compensate for certain behaviors when it comes to the truly uncertain."

The challenge with presenting it this way, is now your rhetorical opponent has something to argue. They can ask you to prove their probability calculations are not accurate enough to be the basis of their actions. However, at this point you are now being tasked to prove a negative.

Because if the probability was the likelihood that a centralized exchange, run exactly like FTX, would have a "run on the bank" (though, of course, not a bank) greater than their assets and/or delays could mitigate is not as simple as trying to figure out coinflips and roulette wheels--of which there are many in existence and whose consequences are generally well known. So to know how far off the calculation was of the result is difficult, to say the least.

And the eventual good behavior that is supposedly sufficient compensation for the naughty/risky behavior is always based on good-behavior results so far in the future, it is on longer time frames than the EA movement has generally existed. Not only would we need hundreds of FTXs in the past, we would need hundreds of SBFs to prosper from them and then see what effect their "philanthropy" had well past their lifetimes.

Then it becomes an ever shifting game of goalposts. Do you compare other utilitarian philosophies that purport using science but do naughty/risky behavior that we generally now accept as immoral? And for whom there never seemed to be a positive/good result? Such as Social Darwinism and Eugenics? EA can argue science is better now. IQ tests are better than, say, phrenology (which doesn't say much). Or do you just dismiss the purported scientific justification part from the utilatarianism, because then you can have a much better sample size, such that you can determine if the justification part is really relevant? Perhaps that would work. Look at all the utilitarian movements throughout history, and see how many of them, regardless of justification, nonetheless lead to massive abuse that negated and went beyond any "value."

But has an argument like the Ricky Gervais' regarding religion on Stephen Colbert's show ever worked? I.e. describe how according to one person's religion those other religions must be wrong, and if so it means that a ridiculously large number are wrong, and yet, despite the odds, that one religion is supposedly right.

Religion is thankfully not utilitarian by default, but when it is used in a utilitarian way (e.g. the Crusades) it is extremely dangerous. And EA when used on large time scales may as well be religiously Eschatological and when done by SBF is utilitarian. And, as is rightly brought up in that TESCREAL essay in a previous substact, that is very dangerous.

But I've digressed. My real point was that one can't simply say probabilities don't exist for the real world. You have to tackle the much harder question of are the EAs and SBFs getting the probabilities right enough for using them as they do.

Edit 10/9/2024 - typoes.