The Fiction of Barbara Fried

Sam Bankman-Fried's mother wrote tales of alienated parenthood and rationalist children. Also: Google antitrust, Pentagon audits, and more.

As part of ongoing research for my FTX book, I’ve been digging into the philosophical and legal writing of Barbara Fried. Next week, we’ll get a deep dive into her die-hard utilitarianism, a worldview that almost certainly led Sam Bankman-Fried into Effective Altruism, and thence to total self-destruction. But about ten years ago, Barbara also devoted some energy to writing poetry and fiction, and today, we dive into those staggeringly rich texts.

Remember that you can support my book, and own a piece of history, by bidding on my courtroom sketches, which I’m auctioning as NFTs, accompanied by physical art, on OpenSea. You can find the above sketch of Barbara Fried here. Bidding starts at around $50 and includes a free lifetime subscription to Flesh/Markets.

First, news in brief.

Google’s App Store is a Monopoly

Google has lost an antitrust suit brought by Epic Games over the dominance of its App Store. Epic has argued broadly that Google used its control of the Android operating system to force partner firms to clamp down on competing app stores – the very definition of an abusive vertical monopoly, and certainly a huge reason Google’s profit margins on the app store are a reported 70%. The case, decided in U.S. district court, is certain to be appealed.

Mickey Mouse Enters the Public Domain (Sort of.)

Starting next year, the Steamboat Willie version of Disney’s iconic character will no longer be protected by copyright. That’s notable in large part because Disney has fought for many decades to change underlying copyright laws to protect its IP, most notably with the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, an absolutely massive government giveaway to the House of Mouse. But artists getting excited should be cautious – according to the New York Times, there will be very specific restrictions on what’s actually free for public use.

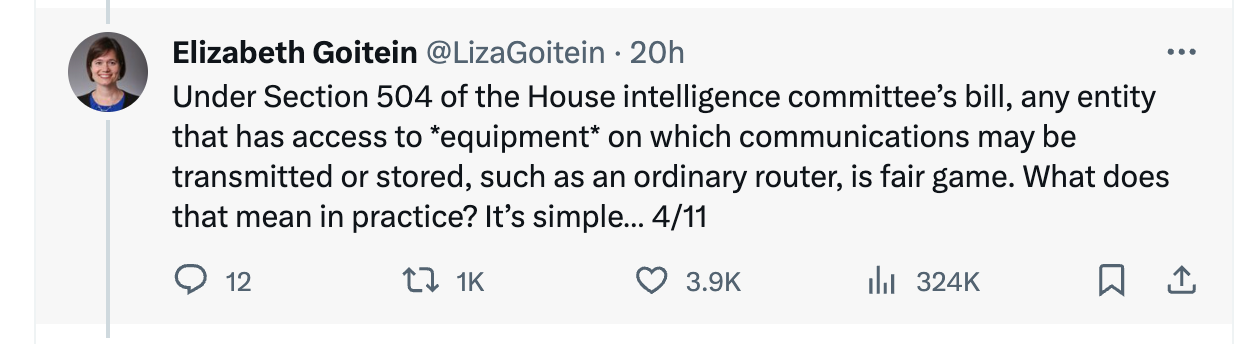

Third Party Surveillance Gone Wild

A House Bill aimed at reforming the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act section 702 appears to turn all data equipment handlers into “communications service providers.” According to an excellent thread from Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice, that means any intermediary who provides internet access could be legally called upon to spy on users.

Pentagon Fails Audit for Sixth Year

U.S. intelligence and military services don’t like facing “oversight” or “accountability,” so it’s hilariously unsurprising that they would nakedly evade something as basic as telling the public how they spend our money. Opacity in government budgeting has long been a huge vector for the abuse of power, and that’s certainly still true today. This becomes even more infuriating when you remember that military spending makes up 12 percent of the U.S. government budget and half of all discretionary Federal spending.

According to Reuters, the Pentagon’s legally-mandated audit “consists of 29 sub-audits of the department's services” conducted by 1,600 auditors who “assessed $3.8 trillion in assets and $4 trillion in liabilities.” Of the 29 sub-audits, only “seven passed this year, the same number as last year.”

The Fiction (And Poetry) of Barbara Fried

Correction: This piece initially described Sam as Barbara and Joe’s younger child. Obviously, he is the eldest. These pieces are effectively rough drafts, and I welcome any fixes you find!

I’ve written again and again about the role that Sam Bankman-Fried’s parents appear to have played in his development and ultimate downfall. Some of these influences are direct and material, like Joe Bankman’s role in bringing Dan Friedberg into the FTX fold.

Some are subtler and deeper. Early in the FTX saga, I wrote about Barbara Fried’s scholarship and its likely influence on Sam. I’m digging back into it now, and I’ve been genuinely stunned to discover just how die-hard a utilitarian she is (or, maybe, was). It seems entirely fair to lay Sam’s enthusiasm for Effective Altruism, and in turn his enthusiasm for high-risk strategies, squarely at Barbara’s feet.

But there’s another way of getting some insight into who Barbara Fried is, and how she thought about her children, before the implosion of her entire life. About a decade ago, when she would have been in her early sixties, Fried dipped her toes into writing fiction and poetry, publishing just short of a dozen pieces in what seems to have been a brief flurry of creativity. Notably, this would have been not too long after Sam left home.

Her work is not bad. At least for the sort of respectable, style-free middlebrow fiction publications she landed in – the University-and-nonprofit backed likes of Guernica and Subtropics. It’s genuinely not bad, that is, and Fried is fairly funny, in a droll New Yorker sort of way. But her work is mostly fairly rote and inconsequential, as art.

It’s far more interesting as self-analysis. Now to be clear, I get that by current standards of literary criticism, it’s sacrilege to search fiction for signs and portents of the author’s life or mind. Creativity isn’t that simple. And most of Fried’s creative work isn’t clearly relevant to what came after. But some of it obviously is.

So we tread carefully, and as respectfully as possible, but we do tread. Because when your kid steals $8 billion, you lose at least some claim to the shroud of art.

Everyone Thinks They’re a Foundling

The one clear throughline of almost all of Fried’s available creative writing is a concern with parent-child relations, and with children seemingly wise beyond their years. That includes this poem from the perspective of a child who is abandoned, then rescued. (Bizarrely, that one was first published in Word Riot, where I also published fiction around a decade ago.) It’s unclear whether Fried’s other poems were published.

But Fried’s fiction appeared in some truly sterling outlets, and it, too, is about parents and children. Notably, much of this was written at around the time Sam would have left home. A natural time to reflect on parenthood.

The most obviously significant piece for our purposes is titled “It Goes Without Saying.” It’s told from the perspective of a child preoccupied with logic puzzles and math - an almost too-obvious proxy for Sam. The child in this story, too, is genuinely interested in their parent’s high-end academic research work.

But what makes this character very tempting to read as a proxy for Sam Bankman-Fried is the denoument of the story, in which a 13 year old narrator consciously rejects her love for her father after he leaves her mother.

“They talk about love as if it were a living thing, like a virus, that gets inside you and digs in for the long haul,” says the pre-teen rationalist. “But it’s not. It’s just an idea about someone, about what they are to you. It exists only because you are willing to think it, and when you stop thinking it, it’s gone. Of course, you can’t always stop thinking something, just like that. Sometimes you really have to work at it.”

It is very, very hard not to hear in this Barbara Fried’s lamenting Sam Bankman-Fried’s native character, already clear when he was around 20 years old: As a person who tried to reject and control his own feelings, but only left them destructively boiling under the surface.

Another Sam-inflected piece of child rearing appears in “What Makes that a Joke?”, the brief story of a father struggling with the urge to be far too rational with his daughter, interrogating her about a nonsensical joke until she cries. It seems like a very clear allegory for the way Sam was brought up - and it already seems clear that Barbara was far more the rationalist enforcer around the house than Joe Bankman.

Some of Fried’s fiction has been lost to the shifting sands of the web, but can still be accessed on the Internet Archive. That includes The Half Life of Nat Glickstein, originally in Subtropics. It’s a genuinely pretty sharp little tale, partly a self-effacing critique of Jewish identity politics, in which a midcentury Jew engages in a fairly comical anti-discrimination campaign against institutions (Macy’s and the New York Times) actually owned by Jews.

That’s mostly notable in that Fried is by all accounts a secular Jew who, as recounted by Michael Lewis, passed little if any of her religious tradition on to her son Sam. The story evolves to recount a breakup in a really affecting way. There’s really nothing to fault about this, as fiction.

The same cannot be said for work Fried published in Guernica. The story “A Song of Longing” is told from the persepective of an immigrant Jamaican dishwasher whose native musical talents are frustrated by her poor upbringing. It definitely betrays some class and racial anxiety: there’s something at least a little strange about a 60-something white Stanford law professor writing a story from the perspective of a young Jamaican housecleaner. The fact that the housecleaner is implied to be a musical prodigy who never got the chance to fulfill her potential is even more tendentious, given that Fried’s own son got the education and opportunies that probably *should* have gone to some less fortunate gifted kid out in the world - and leveraged them to do massive crime rather than to make beautiful music.

Fried’s second Guernica story, “Elegy for Daniel,” is on more solid ground, a short meditation by a character about losing a brother at a young age. I have no idea if Barbara Fried was meditating here on a loss she experienced directly, but it’s bleak to consider a life bookended by losing a brother and a son.

These are all, at best, circumstantial insights. Fiction is just that - fiction. But in her preoccupation with alienated parenthood and rationalist child-rearing, it is very difficult not to conclude that Barbara Fried spent a lot of time thinking about her eldest, oddest child.

These stories, written ten years before Sam’s crimes, were already inflected with the inevitable failure that defines parenthood. As Philip Larkin put it much more concisely, “They fuck you up, your mum and dad. They may not mean to, but they do.”

More than many but less than some, Barbara Fried seems to have fucked her son up in a very specific, even conscious way. If she was already anxious about that a decade ago, we can barely imagine what must being ravaging her soul today, as Sam sits in jail, facing decades behind bars, at least in part as a result of the principles and tendencies she fostered in him.