Sam Bankman-Fried and the Stanford Parent Experiment

Two weeks on trial have shown a Sam Bankman-Fried even more disturbing than we thought we knew. How did he end up this way?

First and foremost, I just want to say: holy cow. Thank you so much to all of the new subscribers who arrived over the last week. I want to specifically thank one new subscriber at the generous “Finance Pro” tier. Right now, all of you are helping me build a machine that will let me keep doing this, and growing it (in particular, I have a podcast in the works). In more prosaic terms, you’re helping me pay my rent. Or, at this moment, about 6% of it. But we’re getting there!

As a reminder, my most generous supporters have made it possible for me to offer a number of free 1-year premium upgrades to existing free subscribers. Find out how here. If you’re a free subscriber, you might want to take advantage of this to read the piece about Sam Bankman-Fried below.

We’ll return to broader news roundups, but I’m spending all day nearly every day locked in a cell phone-free courthouse – and anyway, I know what you’re all really here for.

After two weeks of attending every day of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial in lower Manhattan, I have some thoughts.

The Denial of Depth

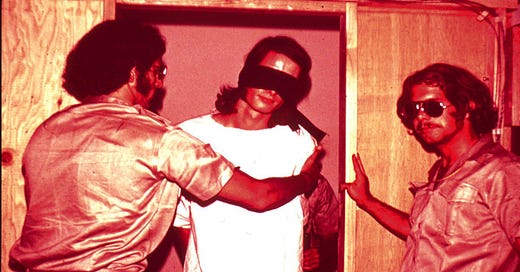

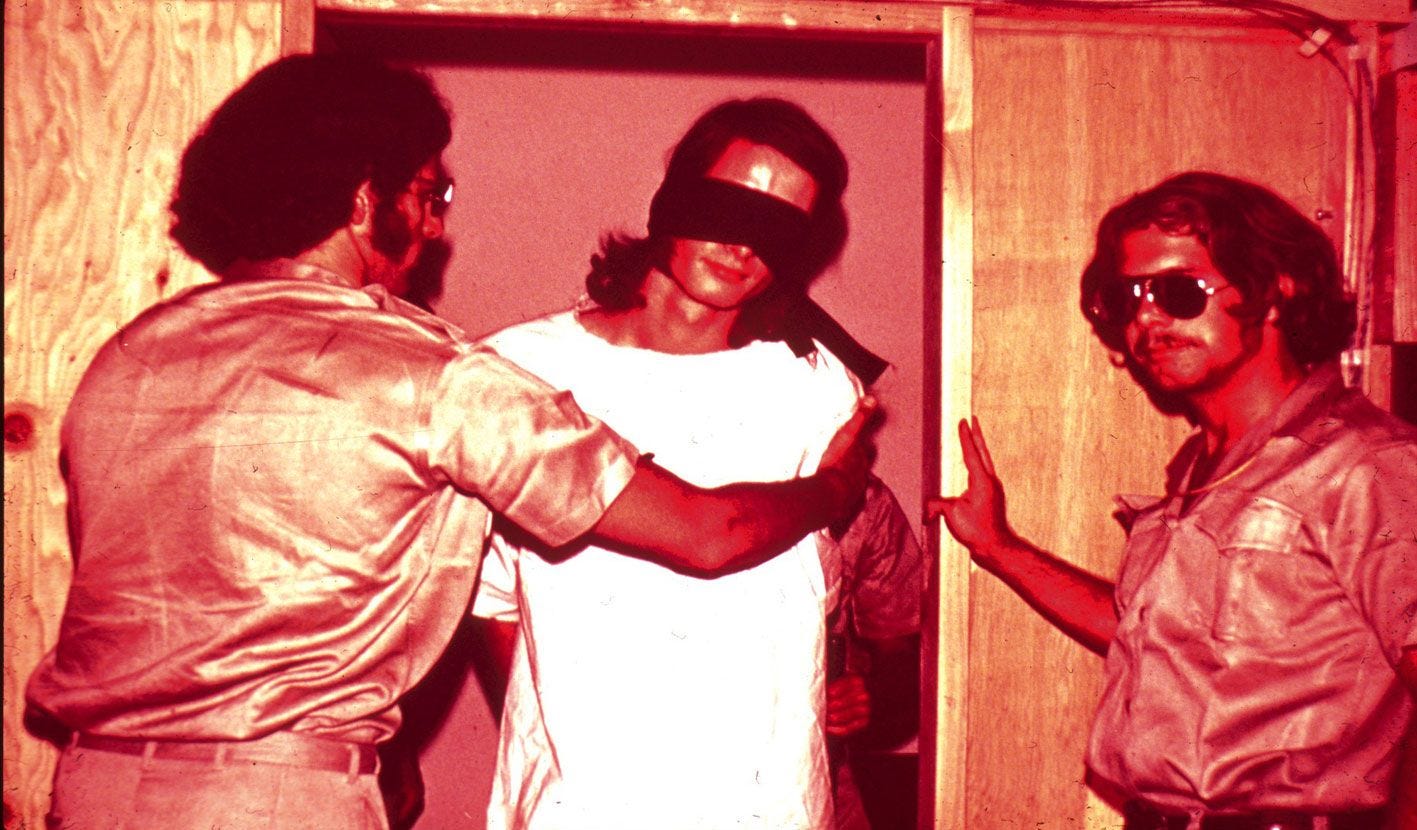

Barbara Fried and Joe Bankman have, as far as I can tell, attended every day of their son’s criminal trial so far. During Caroline Ellison’s testimony, paparazzi chased them out of the rear entrance at the end of the day. During the first day of real cross-examination, Barbara Fried cried, or came close to it, in the courtroom.

It’s a strange thing to bear witness to, so directly and nakedly. I’ve stood in the security line near the Bankman-Fried parents a few times now, and it’s surreal to see them still going through the basic outlines of normal life at a time like this. While Barbara Fried is dour and even menacing, Joe Bankman has come across to many in the courthouse as a jovial, friendly guy.

Normally, you’d have a hard time feeling anything other than intense sorrow on behalf of these rapidly-aging people, who seem to have led at least relatively ideal-driven lives, only to have so much taken away from them right at the end.

But there is something grim and weird and dark to reckon with here.

The first part of that is that, even given that Sam Bankman-Fried did some big-time fraud, the legal decisions leading him to this moment in the Southern District of New York have seemed bizarre – and his parents’ hands are either visible or implied in those decisions. One nuance that got lost for many (including in my own early reporting) is that, while it’s true that Bankman-Fried was never offered a formal plea deal, that’s because his defense team declined to enter negotiations.

We also know that Barbara Fried, for one, has seemed very sure of her son’s innocence, and it’s tempting to infer that she and Joe have shaped his thinking on what actually happened. They are also actively involved in his defense – criminal defense lawyer David Mills, described as a family friend, has been in court with them, acting as a kind of middleman between the parents and the defense team. And it’s hard to imagine Bankman-Fried’s parents didn’t play a hand in picking his legal team, given that they’re paying for it out of a gift from FTX/Alameda (a gift that seems likely to be clawed back sooner rather than later).

The fateful decision to refuse a plea offer, possibly shaped by his parents, has now backed Sam Bankman-Fried into a terrible corner. Not only is his trial decidedly not going his way, his defense team is performing so badly they almost seem to be throwing the effort. Which is strange, because Cohen & Everdell at least have a solid and high-profile reputation.

But there may be more going on here: I’ve seen the defense pursue lines of questioning that suggest they may not actually be getting full and honest information from their client – or his parents.

It may be years before we get any clear sense of what’s going on in SBF’s head right now, but I can only hope that he’s experiencing some kind of violent breakup of his self-conception, one that at least allows him to begin really understanding what he did, and the flaws in his brain that led him to this juncture.

But more deeply, there is the question of what made Sam like this. Between testimony at the trial and reading anecdotes in Michael Lewis’ Going Infinite (a catastrophe whose depths I am still plumbing), my image of Sam Bankman-Fried has darkened dramatically. His complete and self-aware indifference to the humanity of other people is jarringly clear, especially in Lewis’ book, where they are recounted on the way to the author apparently deciding that he loves the guy.

Lewis’ book also offers fascinating but ultimately grim glimpses of Sam’s family life growing up. At least as Lewis frames it, Sam was never interested in much other than math, and his parents eventually came around to the parenting style of ‘treating him as an adult’ as an accommodation to his fundamental nature.

This, as Gideon Lewis-Kraus recently pointed out in the best review of Going Infinite I’ve read yet, is the type of story Michael Lewis loves to tell – the story of an outsider who reshapes the world around him through a mix of brilliance and will.

But Lewis’ book also suggests another reading of Sam Bankman-Fried as a person: That his borderline sociopathy is the product of a socio-ideological experiment run on him by his parents.

Parenting Without Pity

This is an extraordinary, dangerous, and speculative claim. Frankly, it’s the kind of thing I probably would never take the chance of articulating more publicly than in these pages. But this extraordinary claim is supported by some fairly extraordinary evidence.

The basic outlines of the Bankman-Fried experiment are this: What if we taught a child, explicitly and repeatedly throughout his upbringing, that pure rationality held the secrets of life? And, on top of that, that he was more rational than pretty much everyone else? That emotions were a distraction and that his lack of them was a good thing?

Granted, there is also a lot of evidence that Sam was and remained a fundamentally very strange person. Frankly, the better word might be ‘disturbed.’

He repeatedly describes himself to Lewis as having no feelings, no soul, never experiencing happiness, having to force himself to learn how to smile. If there’s one thing Bankman-Fried actually believed about Effective Altruism, it was probably the part about treating the human population as nothing but a set of “expected values,” as calculated at his own alien, genius whim.

Had he not been born to a culturally elite and financially secure family, it’s not impossible to imagine different parents seeking medical or therapeutic help for Sam Bankman-Fried. Instead, Joe Bankman and Barbara Fried moved the world around him, celebrated their son’s strangeness, valorized it, and cross-pollinated it with their own pretty weird strain of liberal hyper-rationalism.

Perhaps the most aching detail is that the Bankman-Frieds don’t celebrate birthdays or holidays. Instead of gifts, according to Sam, if one of the kids wanted something, their parents encouraged them to “have an open and honest discussion about it instead of us trying to guess.”

This strikes me as ominously significant of these people’s views of society. The act of gift-giving is an act of practicing empathy – trying to guess what the other person wants is the entire point. Conversely, the formulation assumes that the gift-reciever, in a totally atomistic and self-contained way, actually knows exactly what they want. Another major point of gift giving is being surprised, sometimes wonderfully, by something you didn’t even know you wanted.

The elimination of mysteries – the mystery of the other, but also the mystery of the self – were seemingly core to the worldview Fried and Bankman passed on to their kid.

Along with that, they gave him the certainty to believe that he had a unique ability to see through everything that normal people regarded as mysteries.

God’s Not Real, and Other Things Sam Knows For Sure

This is encapsulated in another passage in the Lewis book, a discussion about Santa Claus and God, in which Sam realizes that other people actually, really believe in God. This, to Lewis, is a moment in which a singular genius struggles to come to terms with the inadequacy of the regular humans around him.

Sam “simply came to terms with the fact that he could be completely right about something, and the world could be completely wrong.”

This obviously comes through Lewis’ lens, but he seems to have been so drawn into the Bankman-Fried’s worldview that I think we can trust him to speak for them quite accurately. It’s very notable here that he refers to Sam’s superiority as a “fact” that Sam had to “come to terms with,” rather than, for instance, an “idea” that he “arrived at.”

But of course, being certain God doesn’t exist is just as much an act of faith as being certain that he does. But the former places your faith instead in yourself, while the latter acknowledges one’s own inadequacy and places faith in the goodness of the universe.

I say this as a guy who has never been religious and was a firm atheist for about a decade in my twenties: Scientific atheism is the same species of narrow-mindedness as utilitarianism and effective altruism: gestures of gargantuan ego that dismiss the experiences of the broader human species.

We now know where that led Sam: a series of crimes committed seemingly because, as Caroline Ellison testified this week, Bankman-Fried didn’t think conventional moral rules about theft or lying applied to him.

This was apparent long before the collapse of FTX, before Alameda Research nearly exploded in acrimony in 2018, before Alameda even existed. The story is too long to recount here, but Lewis tells of a disturbing incident in which Bankman-Fried gets an advantage on a fellow Jane Street intern on a standing bet. He then repeatedly humiliates the guy publicly by exploiting that advantage.

This led to him getting reprimanded by Jane Street management, which really takes some work in an environment substantially built on competitiveness, aggression and even misanthropy. If the people working a high-frequency trading desk find you off-putting and scary, you have a serious, serious problem.

Of course, there’s also a much simpler way of putting all this: Sam Bankman-Fried was an absolute drooling dumbfuck who got rekt because everyone around him kept telling him he was smart. This is nowhere more clear than in his infamous assessmant that Shakespeare, statistically speaking, probably wasn’t that good.

Henry Oliver at the Common Reader exactly nails this confident idiocy as a symptom of ignorance of the deeper mysteries of human life. Bankman-Fried rejected Shakespeare, and everything Shakespeare stood for - and ultimately found himself ensnared by a fully Shakespearean clusterfuck of parental manipulation and self-delusion.

In a future essay, I’m going to drill deeper on another complex insight the Bankman-Fried’s taught their son to reject - Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the unconscious mind.

Gaze Not Too Long Into The Abyss

This is just the beginning of unpacking what may be the greatest and most fascinating single story of my lifetime. It is unnerving to see a handful of people, up close and in person, who embody so many specific broader phenomena in society. They are still people, but they stand for much more than that.

Often, that kind of transubstantiation is an act of writerly violence, the reduction of a human into features and outlines that are not their synonym. But almost everyone involved in this story – and the Bankman-Fried’s most of all – chose to live their lives as exemplars and leaders of a particular worldview. Parents and son crafted their images around ideas, sold themselves on that basis, and gained influence, power, and wealth.

It feels more fair than usual to read the catastrophic failure of those professed ideals as a rebuttal to the self-righteous, self-important ideas these people claimed for so long to represent.