Venture Capital on Arrakis, Part 3: Money, the Dead Letter

COVID-19 and social death * Confusion is sex * The dollar at the end of time

If I bring any sort of notable personal perspective to the pandemic, it is that COVID-19 arrived as I entered what a lot of people would consider middle age. I’m getting more lethargic and contented and bored at a moment when the world is fostering that, even enforcing it.

In broad outline, we’re living out the plot of a bleak dystopian novel. The death is a steady background hum (when was the last time you really heard it?) that can suddenly rip jaggedly through your own life. But also, you’re already dead, in a hundred large and small ways, locked away in your cell of class-dependent comfort.

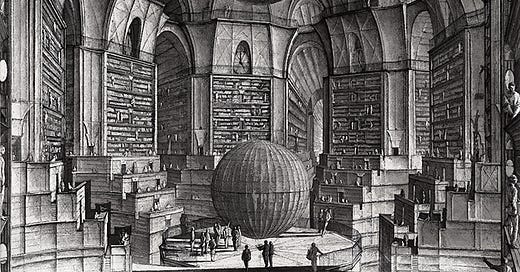

Living here in New York, it’s not a great stretch to daydream of humanity’s future as Borges’ Library of Babel – an infinitude of chambers, stacked miles deep and stretching the circumference of the Earth. In each one is a man, or a woman, with a screen, or an array of screens. These residents may freely step out to their neighbors’ chambers, but they rarely do, and social encounters are often awkward, as each Babelian attends only to their own repulsive and childish niche interests.

This, at least, is what lockdown often felt like for me. But don’t worry. I’m fine. Really.

I know many people have kept up vibrant online lives during the pandemic, and I salute you. I could cite the excuse of having a wife around whom I really enjoy quite a bit, but the truth is I’ve mostly given in to social death.

It doesn’t feel entirely out of step with my life right now – I’m still scrabbling to finish a book and a few other projects that in theory could have benefited from life in lockdown. But I doubt I’m alone in feeling that creative conditions have been suboptimal recently. Pick your excuse.

But notice that feeling you have of your brain slowing down, even as distractions are stripped away. Maybe doing less doesn’t actually leave you more. Maybe abstraction and digital efficiency and the smooth, impersonal interchangeability of everything aren’t the way to go.

What is death?

For the French psychoanalyst and philosopher Jacques Lacan (1901-1981), death, full stop, was nearly impossible to conceptualize. Language and the broader ‘symbolic order’ seemed to constantly threaten death, to be sure, their bare rigidity always trying to constrain the underlying earthy chaos of reality.

But ultimately Lacan saw that this was no fatal threat – not by a long shot. Language, despite its thirst for an all-capturing precision that would truly be the death of experience, constantly fails to fully capture or convey reality. (News to absolutely noone.) That means communication, community, even human selfhood are a series of failed guesses and misrecognitions. These moments frustrate the desire to connect – but that frustration is inextricable from the desire.

For Lacan, language is inefficient and it is deceptive. But it is also fertile, almost sweaty with its missed connections and seductive mysteries (sweaty and extremely French). By mistaking one another – a mistaking practically built into the functioning of language – we constantly generate novelty. To misunderstand is to imagine. Even physical death leaves an echoing trail of signifiers.

But there is an exception to the perpetual fertility of the sign: Money. Lacan considered money “the signifier most destructive of all signification.” The ultimate dead letter – one with no meaning.

Money is the ‘dead letter’ for exactly the reason that it is economically liberating. It creates free-floating wealth precisely because it has no subjective valence. It does not signify anything except abstract value and its social supports. In a gift economy, for contrast, exchange is shot through with intersubjective significance, subtleties of balance and recompense that, while economically inefficient, knit the participants together socially. A money economy instead uses abstraction and precision to sever its participants from each other.

It is the psychic trap of money, and by extension of the numerical sciences that inevitably come to serve it. The dead letters of value and measurement threaten to foreshorten our experience of the immeasurable and ineffable.

The Purloined Letter

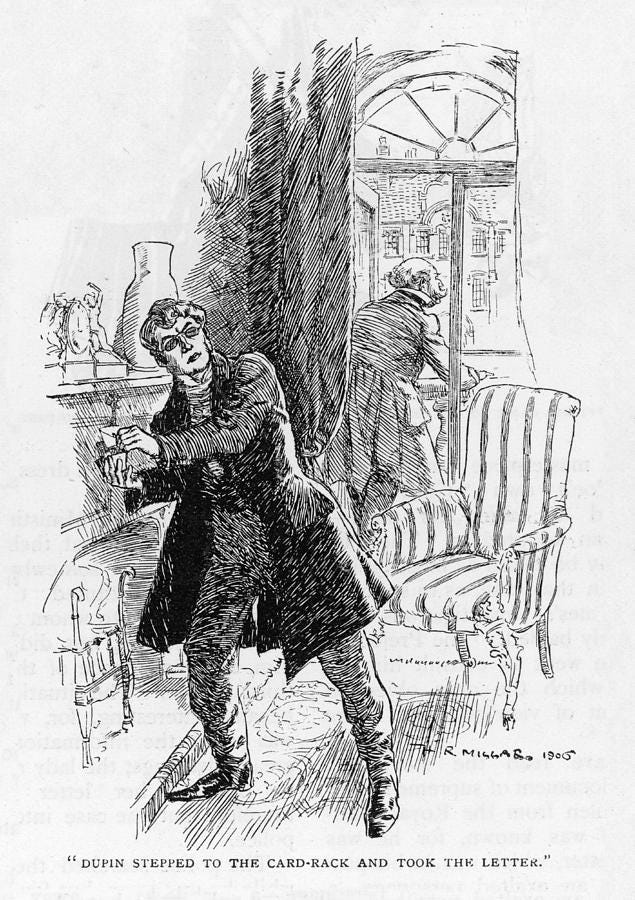

For Lacan, this trap was exemplified in the Edgar Allan Poe story “The Purloined Letter.” It concerns a scandalous royal letter that has been hidden within a blackmailer’s apartment. Two stolid detectives turn the place upside down and cannot find it. Their search is meticulous, down to running knives along the joins in the woodwork looking for hidden compartments. The letter simply isn’t there.

Enter Poe’s Dupin, one of literature’s first recognizable supersleuths, a precursor to Holmes and Poirot. Within moments of a pleading call from the stumped old hands, he has located the letter: turned inside out, crumpled, and stuffed carelessly in a mantle cubby.

The letter evades detection by the naive detectives, Lacan argues, because – like a technical stock picker or a model-driven trading firm – they are fixated on imposing an informational structure on their problem. In this case, they subdivide the room mathematically, and search it zone by zone. But this approach does nothing, apparently, to reveal the disguised letter.

By contrast, Dupin’s canny evaluation of the blackmailer’s mind – intersubjective hypothesizing – not only points him in the right direction, but allows him to engineer a terrible comeuppance for the perpetrator, a nobleman who could well be ruined by the backfiring scheme. There’s considerable strangeness to this element of the story: Dupin’s parting slash at the blackmailer reads like cold revenge, but his motives are left unclear. More importantly, Dupin leaves his signature: the victim will know his destroyer.

Then comes Dupin’s truly final act: He delivers the letter to his sponsor, and receives in return a cheque for a generous number of francs. With this act, he “cashes out,” leaves the game, having fulfilled his constrained goals within it.

What else is death?

Counting is another kind of death. By putting a number on his contract work, Dupin regards himself absolved from any entanglements. But he has also given up his claims to leverage and influence. Mere payment, the dead letter of social stakes, wipes him off the board like dust.

Dupin, like all great literary detectives, is an independent contractor - a man isolated from society specifically by his monetary relationship to it. There is no lifetime employment, no institutional loyalty, for a number. No guilt, no responsibility, no power. And while the lingering taint of Dupin’s vindictive attack seems forgotten, it of course can’t be, in the end. The contractor has assumed hidden risk from the employer, and Poe’s tale ends with the repressed poised to return.

By enumerating the universe, cataloging and measuring its contents, we trade wonder for certainty – but often not even that. Once a thing is quantified, it can seem inert, no longer an object or a being, but a mere fact. Yet its liveness, its unpredictability, are stubborn. Mortgage backed securities are mathematical certainties, until they aren’t.

This is why the cataloging of the human brain, and the automation of its sentiments, are forms of mass social death. What is catalogued is history, a reduction of life to highlights and simplifications. When we catalog history and turn it into an algorithm for the future of our own minds, we only trap ourselves in an eternal present, blinded by precision.

A Terrible Purpose

This is a version of the dilemma of Paul Atreides, the prescient god-emperor of the Dune books. Paul’s own death in the books is somewhat unremarkable. But as strange as it is to say about a figure so central and transformational to his world, he was in a sense dead for his entire life – both because external forces had such a determining effect on who he became, and because he was cursed to foresee so much of where his own lack of agency would carry him.

Dune is so often discussed as a paragon of political science fiction, an imaginitive vision of the maneuvering of great powers. It’s much less often read for what it has to say about class and privilege, which leads casual fans, the kind who might fairly enough assume that Paul is some sort of conventional hero, to overlook three important pieces of context.

Paul is heir to a powerful throne, of course. Royal privilege is the real-world grounding for the science fiction filigree on top: Paul is also the product, if slightly scuffed, of a galaxy- and millenia-spanning royal breeding program whose object was to produce a being capable of more fully predicting the future. This aspect of his greatness was the direct and open dividend of immense wealth and power.

But finally, there is a brilliant element of Dune that must ultimately cripple attempts to turn it into conventional wish-fulfillment fantasy. Paul is able to overcome his family’s betrayers and eventually take over the universe because he is quickly accepted by the Fremen as their leader. This happens in large part because he fulfills a number of mystic prophecies about a powerful redeeming hero.

It’s practically a footnote in the books, but as Herbert tells it, these prophecies were planted in thousands of cultures throughout the galaxy by a vast and secretive galactic organization. The myths are a kind of safety measure for the organization’s agents, who can leverage local superstitions whenever they get in a tight spot.

This is almost exactly how Paul’s character arc in the first book plays out, as he and his mother – a high-ranking member of this manipulative cult – activate a pre-planned ideological coup of the native Fremen.

Paul’s rise, then, is not the achievement of a gifted and special individual, but a sort of galactic C.I.A. operation. It rings true as a specific critique of the shadow imperialism being conducted by the C.I.A. in the name of the Cold War around the time of Dune’s publication in 1965. Antiauthoritarianism is certainly Frank Herbert’s general moral thrust, since the later books show how the heroic myth Paul plays out in the first book transmutes into imperialist genocide, eternal war, and tyranny.

But it is, of course, a bitter pill for attempts to commercialize Dune. There are strange twists and turns in the way it all plays out, but in broad outline Paul Atreides is a fascistic figure, the product of a vast technocracy and its mindfucking ideological apparatus.

These are set loose on a people – the Fremen – whose way of life is smaller, but more nuanced. ‘In tune with nature,’ though in this case nature is mostly giant sandworms. Becoming foot soldiers in a brutal galactic jihad turns out to be one of the brighter parts of how all this plays out for the Fremen, who decline into decadence and ineffectuality as their home planet becomes the seat of Paul’s power.

In short, Frank Herbert absolutely did not intend Paul Atreides to be a hero. And the core of his villainy, or at least his darkness, is his foresight. Being able to see the future dooms him to an eternal present in which he knows he will destroy the world, has destroyed the world, is always destroying the world.

This foresight, in Lacanian terms, is a form of death as sure as money. Money is nothing, the ultimate blank gesture. Clairvoyance is the opposite of money – it is frozen because it is everything. It turns then into now and now into forever.

An Announcement

The pandemic has been our taste of the eternal clairvoyant present, if only in the crushing certainty that the next day would be like the last, that next week would be much like today. Some days I feel like I’m slowing down. Most days, it doesn’t matter.

I’m trying not to be dead yet, though. I’m trying not to be done living in the real future – the future that is unknown. Maybe I’m restless, maybe I’m greedy, or maybe I’m trying to wriggle my way out of my own sense of terrible purpose.

A few of you may already be aware that a couple of weeks ago I left my position at Fortune, which is such a weird thing to do that I’m still puzzling over it myself. But I can let you know here that on Monday, I’ll be starting my new position as Chief Insights Columnist at Coindesk.

I’ll be covering cryptocurrency, but also a wide swathe of related topics from the national debt to online privacy. The position was impossible to refuse: I’ll be providing regular daily context for happenings in the market and the world, and I’ll also have wide leeway to pursue deep, thoughtful, but hopefully lively dives into weird and complex topics. More details to come via Twitter and elsewhere.

Finally, I hope my work at Coindesk will be exploratory and adventurous. But rest assured that this newsletter will remain an occasional traipse into the farthest, most ragged edges of my generally worm-eaten brain.