This week’s sentencing of Sam Bankman-Fried marks a culmination of roughly seven years of my career largely focused on investigating frauds and bad actors – and not just writing about them, but helping enact real punishment for their crimes and misdeeds, while protecting potential future victims.

I helped put Sam away for 25 years, and his crimes were the largest I’ve covered. But he’s not the only one of my targets to end up in prison. I’ve gotten people removed from major roles, or highlighted their sketchy track records quickly enough to help protect people from their cons. In maybe the instance I’m proudest of, my analysis helped precipitate the collapse of Do Kwon’s Terra/Luna ponzi scheme, while also warning at least some people in time to get their money out.

“This is highly emotive and vindictive language. By all means have a view on what went on and the people involved, but I’m not sure calling someone a tumour is particularly balanced opinion writing.”

I want to tell you what that has been like, mostly to inspire and guide other investigators and journalists. You really can make a difference in this world, simply by describing it – and being willing to stick your neck out and take some meaningful risks for what you believe in.

There is ample justification for the rising tide of distaste for the compliant, state-controlled strain of “journalism” that dominates most advanced economies. But done right – that is, when fueled by relentless rage at the injustice of the world, and backed up with hard work and a sharp mind – journalism can still be a powerful tool for genuinely making things better.

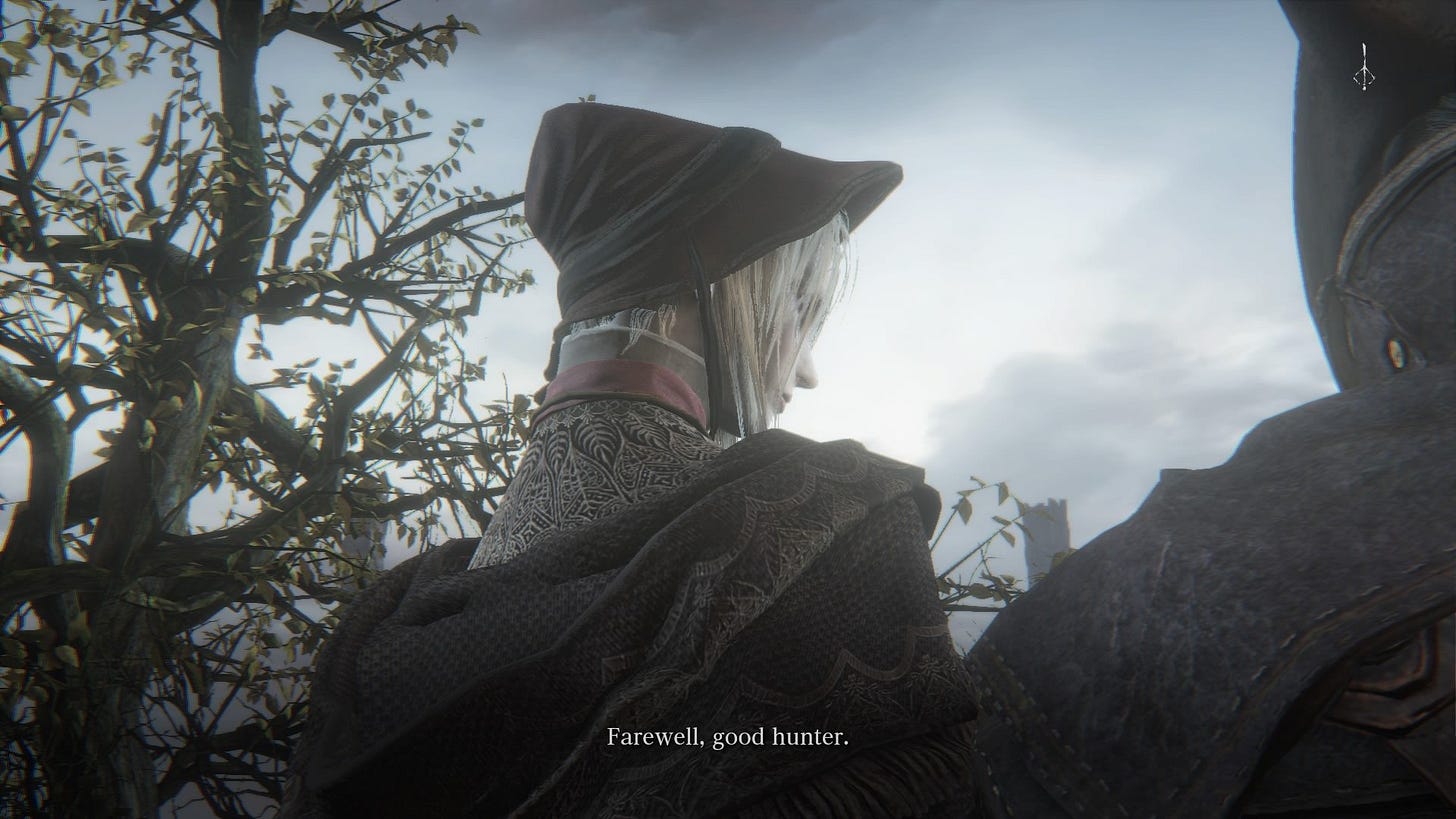

Soundtrack: 50 Cent - “Many Men”

The Most Dangerous Game is Also the Greatest

I want to talk about a few specific investigative projects, to illustrate how all this works and what it’s like:

Fortress Capital and Brightline

(We’ve got Sam Bankman-Fried covered already.)

In all of these cases, described below, I was just one of many hunters. In some cases I was the spearhead of a campaign that relied on the work of other researchers and analysts. Other times, I myself added insight or data to efforts largely led by others. In most cases, the justice system was the ultimate hero of the day (not regulators, though – they do important work, but catching bad guys isn’t generally their strong suit).

It has been a tremendously gratifying run. My work has made me feel tremendously alive, given my life incredible meaning and motivation and velocity. At a time when many people seem to struggle not so much for survival as for meaning, I think that’s an important message to get across: it’s not nearly as impossible to make a real difference as the conspiracy theorists and authoritarians would like you to believe.

It should be said that murking individual con artists is maybe the easiest version of this kind of work. The far bigger investigative heroes, who take much larger risks for often less glamorous returns, are those who investigate and uncover the subtle malfeasance of large institutions, including governments. Unfortunately, the U.S. news industry has almost completely disposed of the type of talent it takes to, say, unearth the Catholic Church’s skeletons. (I’m building Dark Markets in part to help me do more systematic, long-term work of just this sort.)

But it’s also unbelievably intense work, and often outright scary. Journalists are often lampooned these days as soft dweebs or culture-warrior whiners. But that often comes from people who have never experienced the anxiety of putting their name to a serious, major claim. I’ve often said that journalists doing this sort of work are a lot like fighter pilots: the tip of the spear, the first one to get blown up when things go wrong, and not least, adrenaline junkies.

Most of the risk faced by investigative reporters is, admittedly, merely professional. Because you’re taking such big swings, everything has to be exceptionally precise and correct and corroborated, or your own job is at risk. But there are more serious risks: I’ve also done work harmful to people willing to go to great lengths to defend themselves – most notably, Vladimir Putin. I’ve felt the need to take measures to protect myself and those near me, though I’d like to think those were frivolous.

Some may think me gauche for celebrating these wins. There’s a tendency in our day and age to regard criminals and fraudsters as merely entertaining, or even sympathetic. I sometimes wrestle with this myself: is it really good that I helped send some guy to a Balkan prison, even if he was himself malevolent? But sometimes this empathy is a failure to see the forest for the trees: Especially given the moral flexibility that has infested our society, there’s always a need to lay down the law.

There’s something else there, though. Something dark: sometimes it feels good to hurt people. It feels even better when you know it needs to be done. Sometimes what is best in life really is, quite simply, to crush your enemies, to see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women.

But if you let those sentiments drive you forever, they will begin to gnaw at you from the inside. Especially in the social media era, you wind up getting in relentless fights on Twitter. The stress of investigative work hasn’t been great for my family life or my own mental or physical health. So with Sam going away and the end of my time at CoinDesk, it has felt like a necessary time to step back. (On which note: if you need top-tier communications help, reach out.)

Fortress Capital

This was not a magnificent, or even significant reporting effort on my part. But it was one of my first investigative efforts – and it reflected something fundamental about the work. I wrote a reported (i.e. fact- and interview-based) piece on Fortress Capital’s difficulties in fundraising to build profit-driven passenger rail in Florida, where I was living at the time, titled “Even Fortress Capital Can’t Privately Fund Passenger Rail.”

The tenor of the piece helps get at the difference between writing for a magazine, where I’ve basically spent my whole career, and the more-neutral setting of a newspaper. In this and other pieces for Fortune, I wasn’t just disclosing facts – I was making a point.

In this case, I was grinding an axe against a private passenger rail line. I was pro-rail, but I felt this particular corporate-private effort was being oversold compared to the benefit of public funding, and the article was in essence a hit piece celebrating their failed fundraising. As it happened, I was wrong about their prospects: The rail line eventually launched as Brightline, and now runs between Miami and Orlando.

Obviously, Fortress didn’t love any of this – and they expressed that lack of love by complaining to my boss that one of their staffers’ names was misspelled in the piece. I was unbelievably mortified. To have a misfire like that in a critical article is devastating, because you have to (or at least back then you had to) issue a correction that mars the piece forever.

But more to the point, the people speaking for Fortress introduced me to a tactic I’ve come to see as universal: if you’re a big business, you attack every single flaw of a piece of writing, not just a core claim that runs counter to your interests. And you attack these flaws – including the tangential ones – in as ominous and threatening a way as possible.

This is why this kind of work can be so incredibly nerve-wracking – everything has to be buttoned up like a submarine. It requires military-grade informational precision. It’s also one reason investigative journalism is rare – the downside risk is large, and even if you get everything right, you’re going to be harassed, probably by someone with a lot of money.

Not unlike a Wall Street trader, a writer digging for dirt is always just on the edge of getting blown up, reputationally or maybe literally. You wind up wound so tight you could pop.

I won’t lie – I cried for a while when my boss first let me know about this whole misspelled-name thing. I had visions of getting fired that day, or the next. This was very early in my relationship with Fortune, so I really thought my journalism career could just be over-over. I writhed and moaned.

In this case, it turned out to be just fine. I learned that it’s okay to misspell a name every once in a while – it took me a few more years, frankly, before I got in the habit of being truly rigorous about that one.

But eventually you do form those habits. You get names right. You remember what to ask, just to cover all the angles.

All the doors and corners.

“Doctor” Julian Hosp

Not a major or final takedown, but notable because it was one of my first live exposes back in 2019, and you might say it gave me a taste for blood. Hosp was a leader of TenX, an initial coin offering that raised $80 million dollars, then ... essentially did nothing. He also has some sort of not-quite-real doctorate, which is always a fun little sign that someone is trying to con the stupidest people he can find.

Larry Cermak, now CEO of The Block, was really the main investigator on this one, having highlighted TenX’s deceptive tactics well before I got involved. Larry and I worked together to amplify his findings – includingthat Hosp had previously been part of a pyramid scheme called Lyoness. In resurfaced videos, Hosp advised Lyoness marketers to corner and pressure friends into buying into what European courts found was an illegal scam. (The resulting reporting, unfortunately, went offline with the demise of Breaker Magazine.)

Sadly, while these revelations helped pushed Hosp to the margins of crypto, he still seems to have a sizable audience. Based on recent litigation surrounding his projects Bake, Cake Group, and DeFiChain, he appears to still be at best an unreliable figure.

And based on posts like this, it seems he’s still making enemies, disappointing his backers, and spinning it as some kind of Trumpian martyrdom.

Ezekiel Osborne, a.k.a. Zeke Echelon, a.k.a. Zeke DeJong

Sometimes investigative work is scary and stressful. But sometimes you just get to tee off on an evil, incompetent moron, and it’s all worth it.

Just gaze upon this unparalleled toolbox:

A waifish manlet named Ezekiel Osborne paid Forbes Middle East to run a story in which he claimed to be one of the cofounders of Monero. In fact, Osborne had mostly run scammy pump-and-dump groups under the name Zeke Echelon.

This is the essence of the sadness at the heart of these cons - it’s always some guy who thinks he’s fundamentally great, but who hasn’t actually accomplished anything, and so decides to fake it. The story of Zeke Echelon really isn’t much different from the story of Sam Bankman-Fried.

This piece was also part of forming my strong and enduringly negative sentiment towards Forbes, which happily sold its brand to anyone with a spare nickel. Forbes Middle East got scammed by Zeke because they were really an advertising funnel rather than a journalistic operation. (Forbes was also involved, only a tiny bit less reprehensibly, in lending credibility to OneCoin scammer Ruja Ignatova.)

I haven’t seen or heard anything about Zeke Echelon/Osborne in a long time, so this one really seems to have been a kill – though my guess is Zeke is likely still operating in the shadows, he’s at least not hurting a mass retail audience.

Hacking Team and Coinbase

As a driver of what became the “#deletecoinbase” tag, I got a group of Italian Fascists formerly known as Hacking Team fired from their roles overseeing customer data at Coinbase. Hacking Team had eagerly worked with authoritarian regimes, which Coinbase had, incredibly, decided was no obstacle to acqui-hiring them through the security firm Neutrino.

This is probably the one I’m proudest of, both because I can claim a lot of credit for the outcome, and because these men were spectacular pieces of shit who had actively and knowingly helped authoritarians repress their own populations.

It’s also one of the times I felt most directly at risk – these people had already participated in the murder of journalists. A total lack of morals is inherent to the fascist agenda, which pursues only power and control, at any cost. I was later contacted in a vaguely threatening manner by more than one of them. (Unfortunately, this is also one of the stories now lost thanks to the disappearance of the Breaker website. But Michael Casey’s column from the time is a very well done overview.)

Again, while it’s a safe bet these scumbags are still out there doing nefarious things, at least they’re not doing them from within Coinbase’s offices.

So, my message to them: boia chi molla, you worms.

Vladimir Putin

This one was so intense I nearly blocked it out of my memory while working on this writeup.

I reported for Fortune about the ease with which internet users could access child sexual material (CSM) using Yandex, Russia’s home-grown search engine. With help from an extremely helpful source, I reported that Yandex insiders directly blamed Vladimir Putin’s policies for the CSM problem.

Yandex was excluded from a global shared CSM screening service because that service was run by a Western nonprofit. Putin’s resistance to any connection to U.S. or European organizations turned Yandex into a huge and useful onramp for pedophiles seeking CSM.

Reporting this thing was frankly terrifying, even years before the war in Ukraine. I had to discourage someone involved in this story from traveling to Russia soon after it was published, and while I felt paranoid and daffy about it at the time, I think that paranoia has been plenty vindicated.

Trevor Milton

My contribution to this one was modest but hopefully significant. Most importantly, my instinct that Milton was a complete charlatan was correct from nearly the start – and it was based on little more than his bombastic tone and naming the company “Nikola.” The naming thing in particular, with its brain-dead aping of “Tesla,” was so hilariously stupid I figured this guy probably couldn’t spell “lithium-ion,” much less build an electric truck.

But I got specifically suspicious when Milton started talking about some secret new battery chemistry that Nikola was on the verge of releasing on the world. This was at a time when EVs were still new in the public eye, but I had learned that battery research is a very slow, incremental process. So I reached out and interviewed Trevor Milton, for a piece that would eventually be titled “Can Nikola Motor’s Big Battery Promises Be True?”

In the interview, Milton unwittingly revealed to me that his battery claims were hokum. Here are two things he said, from my contemporaneous notes:

“We’re really good at research and technology … now we’re working with groups to commercialize it. And we’re going to hand it over to the whole world. We’re going to turn over the IP to one of the big battery manufacturers and let them sell it to everyone.”

“The problem is we don’t know how scaleable it is, so that’s what we’re doing right now … testing it in weather, various temperature conditions … In the lab we get a few thousand cycles, which is much better than lithium ion. But the real world is much different from the lab.”

In other words, all of this was lab research at best, and nowhere near the market.

Milton, of course, had been lying about a lot of other stuff. Just a few months after my piece, Hindenburg Research had assembled the dossier that would ultimately send Milton to prison for fraud, most dramatically for staging a promotional video by rolling a non-functional Nikola truck down a hill.

Craig Wright and Calvin Ayre

I’ve needled Craig Wright in various small ways over the years, but I never merited a response until I wrote this column, which broadly accused Wright’s backer Calvin Ayre of using the CoinGeek website as a propaganda mill. I am very proud of comparing CoinGeek to the Taco Bell Blog. Naturally, Ayre had some lawyers in the Bahamas or Antigua or something (lol) write up a letter threatening me with some vague legal repercussions if the piece wasn’t retracted.

We didn’t retract it, or change anything – I don’t think we even responded to the letter. There was no follow-up from Ayre. A couple years later, Ayre is turborekt now that a U.K. court has ruled Craig Wright is a lying, psychopathic sack of shit.

William MacAskill

On this one, I didn’t even do anything! I just wrote a CoinDesk column based on reporting in Time that had found that Oxford philosophy professor William MacAskill and other EA leaders were directly involved in covering for Sam Bankman-Fried in his early days. It was an angry column, though! And William MacAskill didn’t like that at all!

What’s most interesting about this incident is that it shows how the powerful live. Rather than actually engage in any self-reflection, MacAskill hired a U.K. reputation management firm to send one of the funniest, most wheedlingly non-threatening threat letters I’ve read in a career full of threatening letters. Sadly, the original document was lost when I lost access to my CoinDesk email, but I have a copy of the text.

It included the request: “Please can this be reworded to make it clear ‘no one has alleged criminal behavior on the part of top EA figures’ as per the TIME article.” Once you have to ask that, you’ve kind of already lost, buddy.

But this is the true all-timer, describing the end of my column (which again, was not changed at all):

“This is highly emotive and vindictive language. By all means have a view on what went on and the people involved, but I’m not sure calling someone a tumour is particularly balanced opinion writing.”

Did calling William MacAskill “a cancer on the face of academic philosophy” perhaps actually go too far?

No, no it did not. Fuck you, Will MacAskill.

Do Kwon

In April of 2022, I wrote a column titled “Built to Fail,” about Luna/Terra’s flawed design. Barely over two weeks later, Luna collapsed.

Let me tell you, this was a head trip. I was writing in the most influential publication in crypto. Did my column help trigger the collapse? Obviously, the collapse of Luna was inevitable – but did I help make it happen at a particular time?

It’s the sort of question that floats over this entire history. Most of the time I’m content to say I’ve helped “bend the curve” of a bad guy’s fate. Do Kwon, though – I take a little extra credit for him. Though as usual I relied on work from other people, particularly that of Ryan Clements, then of the University of Calgary and now a regulator.

This case was illustrative in another way. Much as with Trevor Milton, it was clear to me simply from Do Kwon’s demeanor that something was fishy with him. I used major financial chops to make clear that the entire Terra/Luna structure was stupidly unsustainable at its core, and basically propped up by a ponzi scheme in the short term.

What later emerged, to my amazement, was that far from just being an egotist pushing a bad and fragile idea, Do Kwon had engaged in active fraud and deception early in the project. Over time I developed a theory that, to put it roughly, stupidity and criminality are deeply intertwined. Do Kwon was a major instance of that.

Coda

There are sure to be other bad guys in crypto – they’re working on their next scam right now. We will need watchers, of whatever sort, to help identify them. I’m not sure I’m going to be doing much of that this cycle, or for the foreseeable future, as my priorities shift.

But if you’ve got the Dexter gene, and would like to channel your own unhealthy anger and dissatisfaction into tactical violence against liars and cheats, please reach out. I’ll help any way I can.

Can you create a list of other hunters that you respect? Like Hindenburg Research. Thank you